So what DID you do in the war, Daddy?

This is the time of year that folks say to countless thousands of veterans: “Thank you for your service.” I respond, usually, by saying “Thanks for your support”. Frankly, I don’t know exactly what that means. But I figure it’s okay since I also don’t know exactly what their salutation means. I suspect they don’t either.

This is the time of year that folks say to countless thousands of veterans: “Thank you for your service.” I respond, usually, by saying “Thanks for your support”. Frankly, I don’t know exactly what that means. But I figure it’s okay since I also don’t know exactly what their salutation means. I suspect they don’t either.

Yes, I served. I’m a military veteran. A war veteran. A Vietnam veteran. So precisely what does that mean? In fact, a whole lot of different things to a whole lot of vets of different times, places, politics and other circumstances. It could mean drafted for two years or joined for four years or maybe even 20 or 30; in and then out. That was then, and this is now. End of story. Move on. Or, It could mean haunting, debilliating depression and anxiety, day in and day out, year after year from a torment known as PTSD (Post Traumatic Stress Disorder). Maybe it means chronic or fatal illness from exposure to Agent Orange, the toxic defoliant that the US served up throughout the Vietnamese countryside like crop dusting in the corn belt. Maybe it’s a wounded Purple Heart warrior who is none the worse for it today. Or forever crippled. Or dead.

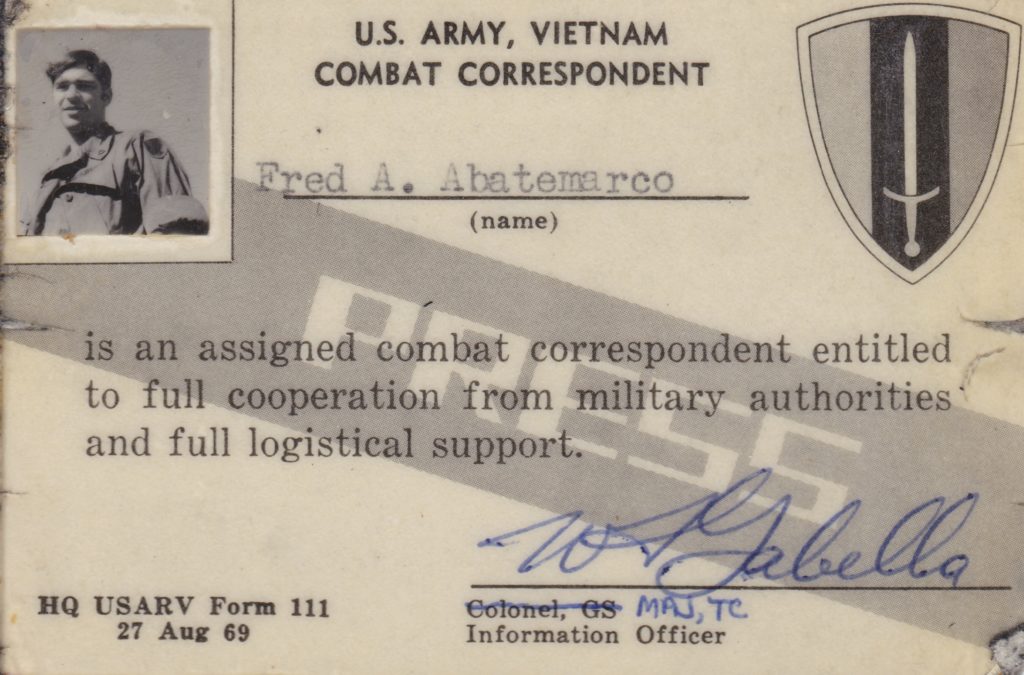

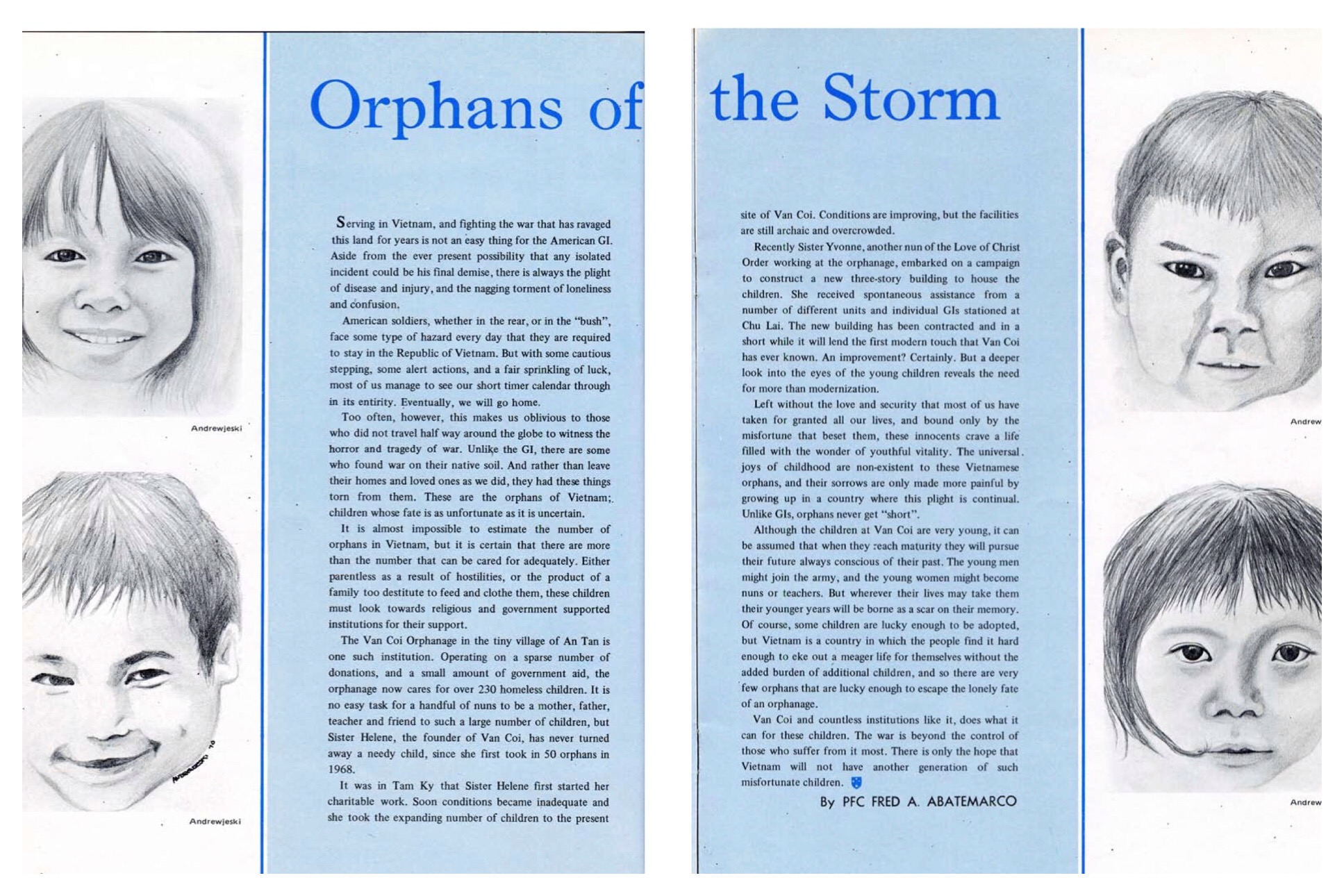

My job in Vietnam was Army Correspondent: “MOS 71Q20” (Military Occupation Specialty: Information Specialist). I was a scribe, not a warrior; More Jimmy Olsen than John Wayne. To the grunts—the infantry soldiers who went to the field to fight—I was derisively known as a REMF. My post was the massive Chu Lai Army and Air base home of the 23rd Infantry Americal Division. I’d regularly go to the field on reporting assignments. But most times, I would “ghost” at the Van Coi Orphanage, right outside the main gate. Sometimes a few of us would take a Jeep on a 10-klick weed run up Route 1 to Tam Ky. With seniority, I gained priority to ride the daily helicopter courier run to DaNang, 100-odd klicks to the north. The Huey gunship traced the winding serene beachfront all the way up and back. The scenery and the breeze was a heavenly respite especially during the hot, humid summer. I had an M-16 always by my side in Vietnam. And when I left our base, I also strapped on a 45-cailiber sidearm. But I never fired on anyone. And the only time I was fired upon was during rocket attacks aimed at crippling our airbase or it’s fuel and ammunition dumps.

I was in Vietnam from 1970 to 1971, a time the war was “winding down”. Troop withdrawals were well underway. The Nixon-Kissenger doctrine was Vietnamization: turn over the politically unpopular war to the South Vietnamese forces so Americans could beat a hasty exit before the 1972 elections, if possible. The Chu Lai area of operation was essentially pacified during my tour. It wasn’t exactly safe. But it was relatively quiet compared to the deadly fighting times of 1968 and 1969.

My experience in Vietnam was more common than you might think. Throughout the war, the ratio of REMF’s to grunts in Vietnam was roughly 9 to 1. Yet roughly half of the 2.75 million troops that served in Vietnam were regularly exposed to enemy attack. But as a Vietnam vet, I am a rarity of my generation. There were 27 million American men of draft age during war. Only 40 per cent served in military; of those, one in four went to Vietnam. And of those, only one in 10 had a combat assignment.

My typical day began at daybreak and ended at sunset. I slept on a bunk with a mattress below me and a solid roof above. I ate hot food–such that it was–in a mess hall. Mostly I worked inside a rickety tin-roofed hootch–a building made from 2×4’s, plywood and corrugated metal sheeting–which served as the division’s Information Office. I cranked out “news” stories, feature articles, press releases, and action reports for our base newspaper, quarterly magazine and for dissemination to other military and civilian news outlets. Orphanage stories were my specialty. I also escorted civilian news correspondents, politicians, sports and entertainment VIP visitors to and from the firebases and remote landing zones of our area of operations; Quang Ngai and Quang Nam provinces.

For a while, I had a night job producing the “Americal News Sheet“, or the daily “kill sheet” as many called it. Each evening, field units called in their day’s actions which I dutifully summarized. Then I’d pick up sports and general news from Armed Forces Radio and finally add which ever “public service” ditties–stay off drugs, get checked for STD’s, reach out to the mental health help line–the brass was pushing. Once I reproduced this two sided broadsheet on an old fashioned Mimeograph machine, I delivered a couple of hundred copies all around the base mess halls and hospitals. The docs and the nurses were never happy to see me. For my authorship, they scorned me as Dr. Death. But the cooks in the mess halls were happy to get the sports scores–albeit as much as 48 hours late.

After work, I’d hang out at an unofficial bar we called The Hog Farm, set up by a bunch of us REMFs in the back of the G3 Operations hootch. The Hog Farm was a co-op of sorts. About a dozen of the regulars chipped in our monthly PX rations cards which entitled us to purchase a fixed amount of beer and booze. Everyone was welcome at the Hog Farm and no one ever drank alone or paid for a drink. But we had a strict rule of no war stories. You could talk about home, your girl, your dog, your car, your truck, whatever! But absolutely no war stories.

I tried hard to keep my nose clean and head down until my time in Vietnam was done. I came pretty close to succeeding. But one evening, I was caught AWOL from my post and that was essentially the end of my cushy night duty. My punishment was a field assignment north near the DMZ—Quang Tri and Dong Ha—where the Americal Division was flying air support for the South Vietnamese Army’s attempt to reopen Khe Sanh and push into Laos to cut off the Ho Chi Minh trail.

Operation Lam Son 719 took place late spring 1971. I flew a lot of combat and support missions in what was the largest air-mobile operation of the war and in the history of warfare at that time. Not anything like the pleasant and peaceful chopper rides up the coast to Marble Mountain that had been my norm. Unlike my time in Chu Lai, the DMZ was bloody and dangerous. But I survived that operation and all the rest. Eventually, I made it home unscathed. I was among the lucky ones.

My Vietnam service was hot, nasty, dirty, stinky, buggy and as uncomfortable as I ever have been. It was lonely and scary. But it was a lot worse for so many others who served. Here’s a brief description of what day to day life was like for most grunts in the Americal Division at the time.

“We spent 18 days in the bush. No showers very few even shaved. Gave each other hair cuts. After 18 days we would rotate back to the fire base as security for about 5 days and then back into the bush for another 18 days or so. Every 3 months we would get a couple of days for a “stand down”…. beach, steaks, band and girlie shows, letting leech and saw grass lesions heal. Got to sleep in a bunk. Then back to the bush for another 90 days of going around a 20 klick or more diameter circle around the fire base. Rinse and repeat.”

So if you want to thank me for my service, I will accept your salutation with as much grace as I can muster on behalf of all my brother and sister vets of the Vietnam war and others; on behalf of those who made it home and those that did not. And for those who still bear the wounds of war today. I will say back to you “thanks for your support”. Silently, I’ll hope that we each do everything possible to figure out ways to stop doing this warfare thing anymore. That would be ideal service.

Fred, I will thank you for your service as well as for your vivid description & candidness of your experiences! You are absolutely correct that while many of us served (some in less hostile environs), there are many real heroes that deserve more credit for their contribution and valor.

I guess I say “Thank you for your service” to people that have served because:

A. I didn’t serve. When it was my time, we were at peace, and the volunteer military was just finding its feet. I regret not having served.

B. My dad, my uncle (his brother) and my grandad all served. They were grunts and saw front line action. They were forever marked by the experience, and their families suffered for it, just as they did. Warfare is hell, and it’s not getting any better. It leaves indelible marks on the survivors. They may not be visible, but they are very much there.

C. I don’t know what else to say. I want my kids and other young people to know that to serve is putting yourself out there for whatever happens, no matter your intended MOS. For the chance you might not come back, or you might come back forever marked by the experience, or not. For that, you deserve to be honored/recognized by your fellow citizens that enjoy the fruits of your efforts.

I too hope that the world’s second oldest profession becomes a thing of the past. While there people performing heroic acts, there is nothing heroic about warfare. It destroys. It does not build or rebuild, or make the world safe for democracy.

Here is to that day when we can find another way to resolve our conflicts.

Hi Fred,

thanks for the post. Your topic is interesting and I hear it often. I should say I did not serve in the military. I was married with kids before the serious war effort started. An odd thing happened to me once about 20 years ago, flying home from HNL to Portland OR and I had visited Pearl Harbor that visit and was wearing one of the blue caps with USS Arizona emblazoned on it with gold leaf etc. A woman boarded the plane, was passing me when I was seated and tells me “thank you for your service”.

I immediately started to explain ‘I didn’t serve! I am wearing this cap out of respect to those who died on Dec 7, 1941! I wasn’t even alive on that day!’ – It totally caught me off guard as I have never claimed to have served in VN or any service, I never accept “Veteran discounts” etc. I later wondered, do I look that old?!

After getting home, I put the cap up and have never worn it again!

So, I too have had odd reactions when I hear one tell another that expression.

May we never have another war.

regards

Mickey

Maybe Thanksgiving is as good a time as any to thank everyone who served or serves, by choice or chance, for doing dangerous work we’d prefer not to do ourselves. Whether you agree with the mission or execution of this war, or any war, it’s clear that freedom is not free, and equally clear that some pay a higher price than others. Thank you, Fred. And happy Thanksgiving!

Hey Fred, I drew the two kids on the left… I don’t know who did the ones on the right, but I was credited, anybody know? re: Orphans of the storm kb doc is now over… I’m done, for now, I ended up digging into my viet stuff, I feel really over exposed.

SKI