Early on March 16, 1968, the massacre of hundreds of innocent women, elderly men and children by US soldiers in the tiny hamlet of My Lai took its place as the Vietnam War’s most enduring badge of depravity, and the hapless Americal Division’s most unholy ghost.

On March 29, 1971, I listened intently from my Chu Lai hootch in Vietnam, as Armed Forces Radio announced that Lt. William L. Calley, Jr. was convicted of multiple counts of premeditated murder of Vietnamese civilians three years prior in the tiny village of My Lai.

My Lai was well known to me. It was a only short helicopter ride south of my base; a place I had gazed down upon from the air many times flying by helicopter to one Public Information Office assignment or another for my unit, the 23rd Infantry, “Americal” Division. Calley was also an Americal Division soldier. He was the platoon leader who led the My Lai assault, and turned it into a brutal massacre in 1968.

When the Calley verdict came to call –one of the most unholy of the many ghosts which haunted the hapless Americal Division–I was only three months in country. But I was already wise to the countless sins of the Vietnam war. They were all so near at hand. Virtually all the barbarity which was turning the hearts and minds of Americans against the war had been visited upon my division. Drug use and racial strife was rampant. Fragging murder attempts on officers by their own troops were occurring once a week. The countryside outside our gates had been withered to an ecological apocalypse by the herbicide defoliant, Agent Orange. The sight of plastic body bags containing the remains of US soldiers killed in the sneak attack only one day before at our remote Fire Support Base MaryAnn — where more than thirty US soldiers were killed and eighty-plus were wounded–were still fresh in my mind’s eye.

Oceanview not withstanding, the Chu Lai base–the Americal Division, the war, the Washington politics that kept it going–repulsed me. And the news of Calley’s verdict on this day only served to deepen my bitterness, with its reminder of the Americal Division’s most enduring badge of depravity: the atrocity that occurred at My Lai.

It was a typically hot, dusty, post-monsoon morning when Calley’s operation kicked off on March 16, 1968. Shortly after sunrise, 136 soldiers of Charlie Company, which would spearhead the specially formed Task Force Barker, were inserted by chopper into a rural farming community that the Army called Pinkville.

The unit had patrolled often in this Quang Ngai province area. It was considered an enemy stronghold. Charlie Company had suffered casualties by sniper fire, machine guns, and booby traps. The day before the operation, the men held a memorial service for their fellow soldiers killed during the preceding weeks. Battles of the Tet Offensive uprising a month before were still fresh in their memories, putting the soldiers on edge.

The assault on Pinkville would be led by Calley’s 27-man First Platoon on point. Intelligence reports indicated they would almost certainly encounter seasoned Viet Cong resistance, possibly even a battalion-size force of NVA. The objective was to “engage and destroy:” burn the hootches, slaughter the livestock, poison the water wells, lay waste to field crops and food stores. They were not expecting civilians.

After landing, Charlie Company advanced toward My Lai’s cluster of thatched huts. They searched for the enemy and weapons. They found none. There were only women, children and elderly men in the hamlet. The soldiers rounded up these civilians in groups. There was no resistance. No one fired upon the soldiers. Regardless, Calley ordered his men to begin shooting the villagers.

There was pushback from some soldiers. But Calley was insistent. Approaching one young private who had dozens of old men, women, and children under guard, Calley instructed, “You know what to do.” Then he left. When he returned after a short while, Calley asked why the villagers were still alive. The soldier hadn’t known Calley meant they should be shot. Calley declared he wanted them dead. They both opened fire on the group with automatic weapons. The young private cried. All but a few children fell. Calley then personally shot them with his M-16 rifle.

The gunplay became widespread. Mothers shielding their children were shot. When the youngsters tried to run away, they were picked off like wild game in a pasture. The soldiers machine-gunned farm animals, gang-raped women, tortured the living, and mutilated the dead. They burned the village to the ground. Calley personally dragged dozens of people, including babies, into a ditch and executed them. He interrogated a Buddhist monk and then shot him in the head.

Before lunchtime, as many as 500 defenseless noncombatants were systematically murdered. The majority were women—nearly a score of them pregnant. More than 150 dead were children, including dozens of infants. A precise number of casualties at My Lai has never been fixed. The bloodshed only stopped when an Army helicopter pilot on a reconnaissance mission landed his aircraft between US soldiers and a group of fleeing villagers. Warrant Officer Hugh Thompson ordered his door gunners to open fire on Charlie Company if they did not break off the attack.

Officers in charge were initially praised and awarded medals for the Pinkville operation. The crimes at My Lai were covered up for more than a year. Shortly after I was drafted in 1969, I was heartsick to read about its brutality. Photos of the carnage, taken by Ron Haeberle, an Army correspondent much like myself, broke the story to the world. His images of torn, lifeless bodies scattered in irrigation ditches and trampled fields embedded the profanation at My Lai into my soul for the rest of my life.

Today, the site of the My Lai massacre is known as the Son My Memorial. It was an essential stop for me when I returned to Vietnam in 2018 with Natalie. I stepped upon those horridly hallowed grounds–familiar to me in 1971 as tranquil farmland, punctuated by banana trees and pepper bushes–brimming with emotion. Dominating the site now is a larger-than-life “never again” limestone sculpture, which struck me as a mash up of Tommie Smith’s and John Carlos’ Black Power salute at the Mexico City Olympic Games, and Michelangelo’s Renaissance Pieta at St. Peter’s in Rome. There is defiance in its up-stretched, clenched fist. But also tenderness in the effigy of a mother cradling her lifeless baby. So perfectly in c character of the Vietnamese people as I had come to know them.

When we visited the Son My museum, a soft-spoken young girl in a royal blue ao dai tunic stumbled through a canned-English presentation. She attested with little emotion to the wartime atrocities committed there decades before she was born, reciting haltingly the captions of blurry pictures, which served as a faded record of a story the young woman could never adequately convey. The story of a day when an innocent village became hell on earth, evermore to symbolize the terror, cruelty, and madness of war.

The teenage girl’s drone was strangely soothing to me, like a chant. It calmed the rage that welled up in me as I reimagined the atrocities of Calley and his men. It was balm for all the other sorrow which was stuffed deep down inside me, scarred over and dormant since my return from the war. I wished at that moment there was a censer on hand at an altar, like so many that Natalie and I saw in the pagodas and traditional homes we visited. I wanted to make an offering–a prayer for the memories of My Lai, and MaryAnn, and all the rest–that would waft up and away like smoke, banished into the ether.

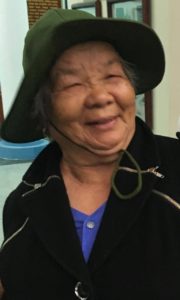

Suddenly, loud, staccato Vietnamese assaulted me from behind, shattering my brooding. I turned to encounter an aged, fleshy woman, overdressed in a dark wool coat and wide brimmed hat. Her rapid-fire torrent made me fearful that I was about to single-handedly take the fall for the cold-blooded crimes we were reliving on the museum walls. Natalie and I were the only Westerners in the room. Oanh, my guide and translator from DaNang, rushed over to rescue me. But it turned out that Mrs. Thong Chi Nguyen, the enthusiastic speaker whose loud barking had startled me, simply wanted to tell us her story.

“I am back here after 51 years,” she said. Thong lived nearby the My Lai community before the war. When fighting in the area intensified, she and her husband moved to the Central Highlands province of Dac Lak. She was 39 then. Word reached Dac Lac about the massacre at My Lai and Thong never returned.

Thong’s husband was a Viet Cong “Chieu Hoi”, who surrendered to the South Vietnamese army. “It was too dangerous, too risky, for him to fight the war against the American forces,” she explained. After the war, Mr. Thong paid dearly for his “welcome return.” Defection from the Communists cost him nine years in prison. He died at 68.

Mrs. Thong, who was 90, told me about her sons and grandchildren. They carry on her family’s legacy. But none of her old friends from My Lai survived. On this day, she viewed a wall inscribed with the names and ages of more than 700 victims, many of whom she knew. “There is no one left,” she said to me without lowering her voice.

I was bewildered that, punished twice—the toll of the war, as well as the retribution against her husband—Mrs. Thong expressed no bitterness. She enjoys modern Vietnam. “Now, I am free to travel,” she boasted with a laugh and a smile. Even if her travel is only to a place she once lived long ago, where everyone she knew no longer exists.

I envied Mrs. Thong’s ability to overlook the loss inflicted upon her, her family, her country. Or had she, more accurately, overcome it? Was that the real lesson? The Vietnamese are better off now, not because of our intervention into their struggle, but despite it. They honor the dead. Live in peace. Look forward. If only we could do the same.

The news of Calley’s conviction that morning on the base at Chu Lai gave me some hope that at long last, one wickedness of the war—of the Americal Division—had been atoned. The military judges at Ft. Benning sentenced Calley to life imprisonment, finding him personally responsible for the murder of twenty-two civilians. However, President Nixon got him off the hook. Calley never served a day in jail. Nor did his commander, Captain Ernest Medina, whose orders Calley said he was obligated to follow.

A total of 18 other soldiers were prosecuted for crimes at My Lai. None were ever convicted or punished.

On April 28, 2024, at age 80, Calley died of undisclosed causes in Gainesville, FL. One ghost of the Americal Division, had finally been exorcised.

As my name indicates, I’m just a dumb***. But I find your general take on war, atrocities, horror and survival enlightening. Allowing for the ability to move on and to not be paralyzed by the poor decisions that led to such situations. Even allowing for forgiveness, I feel.

You’re a good man Fred.

On a present day note identifying the fact we have moved on, the USS Carl Vinson just arrived in Vietnam. While I’m not sure you are in the same part of the country, I know a crew member. Ask for Hunter Belmont if you encounter crew.

Until next time……

cooling machine!

Good analysis of the statue and the banter and tone of the young woman’s voice. Nice that you were comfortable enough to pay your respects. I am sure you and Natalie are doing it justice. Carry on.

We are in fact same place–DaNang. But we’re not making public appearances beyond the seafood restaurants.

Can you feel my tears. We were all against the war but it did not matter. Deja Vu.

What a marvelous gift ? for you to meet Mrs. Thong to share your stories. It’s the human condition that helps bring the balance in the universe. So glad u traveled the distance to experience a different Vietnam ?? and enjoy the people & cuisine.

Safe Travels!

PS: you r missing another winter storm; we start heading driving home tomorrow 3/8.

Thanks for your service to our country Fred. Thanks for sharing this beautifully written travel journal laced with incredible descriptions of your sights, smells and feelings. Continue to enjoy your trip – especially the interesting food! Safe travels to you and Natalie.

Una testimonianza dello spirito umano! Signora Thong, specialmente!

Thank you for your unflinchingly honest take on your visits, FA. Even though I have “known” of this incident for years, it was only in the recent Ken Burns PBS documentary that I understood the full horror of what happened.

There were indeed many more and many after, but they didn’t always involve a world power, and the power of a new visual medium out in the field. So maybe you visited not just a memorial to My Lai’s victims, but a rememberance of all civilians slaughtered senselessly of all times and places.

È vero! Grazie!

Think Syria, etc.

The Ken Burns documentary makes an interesting story in and of itself here in Vietnam. It is officially verboten. However, the firewall in Vietnam is very loose. Everyone who cares, finds a way beyond it. Many folks here have seen it and most are so young, that they have little knowledge or understanding or even interest in the so-called American War. Many here did not know about My Lai until watching this. I am amazed. But you and I will talk further. Because as good as the KB doc is, it didn’t tell the whole truth. The political retribution of the North was horrid and cruel and as terroristic as anything committed by the south and Uncle Sam.

Soon we will be on our 9th visit to Vietnam. 10th for my husband who was a very young (19) USMC radio operator in the Chu Lai area in 1968. He was hesitant about the first trip I planned 12 years ago. Now it’s a favorite place to visit. We have made it to Chu Lai to see how it looks. The American war (as it’s called) is not an issue any place we’ve been from north to south.

I wish I hadn’t waited so long before my first return. If you are heading back to Chu Lai area on your next visit, think about contacting Mr. Cau Nguyen Huu, who was a Vietnamese translator for the 196th Infantry, part of the Americal Division, back in the day. He was very helpful to me, scouting the base, and recalling many of the outer firebase and LZ locations. He is at caunguyenhuu1945@gmail.com. Have a great trip. I’d love to hear more.