A handful of distinct reasons made our ad-hoc Hog Farm bar in Chu Lai unique. No one ever drank alone or paid for a drink. No one was ever turned away, any time of day or night. And most important, there were no war stories allowed.

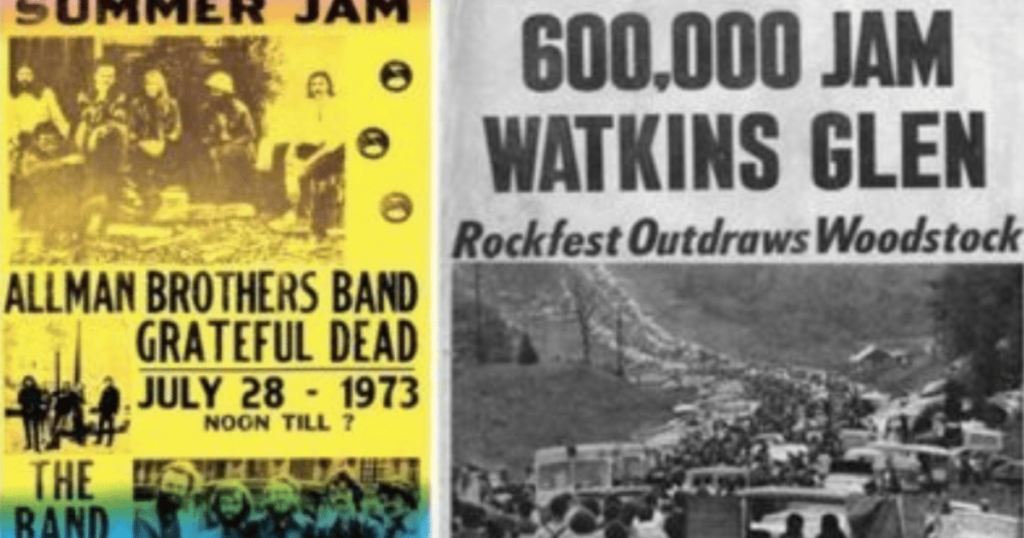

The flashback came unexpectedly. I was home from Vietnam for more than three years. I’d graduated college, gotten married, and was working in my chosen field as a reporter for the Elmira Star Gazette newspaper in the tiny town of Watkins Glen, NY, population around 3,000. “The Glen” is perhaps most famous for the Summer Jam Music Festival that took place there in 1973. Three iconic rock groups, the Allman Brothers, the Grateful Dead and The Band, attracted a world record crowd of some 600,000, forever putting the tiny burg on the 20th century pop culture map.

But the site of that concert, the Watkins Glen International Race Course, was already justly famous among a worldwide audience of motorsports fans. It was there at The Glen, each fall, that the final contest took place in the most prestigious car racing circuit of all: Grand Prix Formula One.

In October, 1974, the US Grand Prix featured a rare end-of-season climax: Clay Regazzoni of Switzerland, competing wheel to wheel against Emerson Fittipaldi of Brazil. At the end, one of these drivers would be crowned world champion of the entire 15-race season. To witness this moment—the international four-wheeled equivalent of a World Series Game 7—my little upstate NY town was literally bursting with racing fans from all over the world.

Jaunting along shoulder to shoulder with the crowd one afternoon, the sidewalks crowded that race week like Fifth Ave. during the New York City Christmas shopping season, the back of a young man’s head caught my eye some 20 yards ahead. He towered above all others. Shiny black hair. A long skinny neck and gangly gait. He seemed familiar. He looked like… Nah, not him, not here. Or could it be? I started to convince myself it was him. It was Bitch!

“Bitch! Hey Bitch! Wait up Bitch! It’s me, Fred. From Chu Lai! How you doin’ Bitch?!” I elbowed my way to him as I shouted. He turned. We both stared.

It wasn’t Bitch.

Mistaking someone’s identity–especially when you think their name is Bitch– is, well, a bitch! I was crimson. But if I can make you understand who Bitch was, perhaps you’ll agree that my public humiliation was worth the risk. I knew Bitch—though never his real name—in Vietnam. He was the Head Hog. That is to say, he was chief bartender and proprietor of the Hog Farm, the most unusual and unofficial watering hole on the sprawling Americal Division base at Chu Lai, where I was stationed during the war.

The Hog Farm is what kept me sane in Vietnam. Certainly, there were plenty of other places on the base to have a beer, a whisky—or more than one. The EM Club for enlisted soldiers, the NCO Club for sergeants, or the Officer’s Club for the brass. They all served drinks, snacks and food, had a juke box and often live bands, terrible as they might be. If it came down to it, you could always swig warm brew or tip back the bottle in the privacy of your own hootch.

For a small handful of reasons, however, the Hog Farm was unique. At the Hog Farm, no one was every turned away any time of night (it did not operate during normal duty hours). Also, no one ever drank alone or ever paid for a drink. For those pleasures, there was a single caveat from which all decorum flowed: “No war stories.” A sign behind the bar said so. And Head Hog was there to remind anyone, when necessary.

I’m not sure who set up the Hog Farm or when. It was there before I arrived in 1970, and was still going strong when I left in 1971. When Bitch rotated home, a new Head Hog was chosen to carry on, just as he rose from the 2nd in command “Littlest Pig” position in his time. It was definitely a word of mouth thing. You knew about the Hog Farm or you didn’t. There was no secret handshake, nor was there a signpost. It was unauthorized but not illegal. The Hog Farm operated in plain sight, literally in the backroom storage area of a very key strategic Division war office—the G3 Operations hootch where, by day, maps and troop movements were created, analyzed, and otherwise fussed over. But at night, it transformed to an oasis of temporary salvation.

The Hog Farm was a co-op of sorts. About a dozen of us regulars stocked the Hog Farm’s bar by chipping in our monthly PX rations cards. These entitled us to purchase a fixed amount of tobacco, beer and booze. A rare luxury on our huge Chu Lai base was a PX (Post Exchange) store that rivaled a modern day Costco. We’d pay for the Hog Farm’s monthly supplies with the voluntary contributions made at the bar. The tips jar usually overflowed by the end of each night without the slightest urging. If you were flush, you stuffed the cup with however much MPC you wanted to unload. If not, you drank on the arm. No matter. No judgement.

The proviso that no one ever drank alone was sacrosanct. Head Hog actually created a bunk room for himself in a portion of the G3 hootch, so he was there to belt one back with you even in the oddest wee hours. It mattered not if you were coming off an overnight operation, were wakened by a rocket attack, the snoring of your bunk mate, or the gnawing of cat-sized rats.

One nasty stormy night, I filled in for the official Head Hog who was enjoying an R&R respite in Bangkok. When the regulars left around midnight, I tucked myself under the scratchy army blanket on Head Hog’s bunk, and was off to the land of nod in no time. A few hours later, the spring-hinged hootch door opened, the cold and wet monsoon night intruded and I awoke. There, stamping the wet muck and mud off his boots, stood a soldier I never met. A dripping wet steel pot helmet shaded his face. His M16 rifle, slung beneath his soaked canvas poncho, pointed downward. He had just finished guard duty and was looking to wind down before heading off to bed. He’d have half the morning off to sleep, but I would not. Still, a Head Hog must do what a Head Hog must do. I rallied from my slumber and joined him for one or two or who remembers how many drinks. We listened to Bob Dylan’s New Morning album, and shot the shit about things long since forgotten.

The back door to the G3 hootch was never locked. Once inside that ramshackle room, an open doorway directly ahead–festooned with a colorful beaded curtain–led into the cramped and unventilated Hog Farm. No bigger than 10 feet deep and 20 feet wide, it comprised a back shelf counter, a dry bar with a dorm-room style refrigerator, cases of beer, liquor and soft drinks stacked below. At the far left of the bar was the Hog Farm’s nerve center: an all-in-one modular stereo system that played records, cassette tapes and AM/FM radio. Another great PX score. We played The Animals, Led Zeppelin, Elton John, James Taylor, Jackson 5, Diana Ross, Beatles, the Kinks, Curtis Mayfield. There was a whole bunch of country music too, by Merle Haggard, Charlie Pride, Johnny Cash, Roy Clark, Tammy Wynette, Mel Tillis, Loretta Lynn.

A few strings of Christmas lights and a neon Pabst Blue Ribbon beer sign lit the room, barely and eerily. Bamboo screens hid the two-by-four and plywood walls. We had bar stools, even a sofa. It wasn’t quite Rick’s Café Américain from Casablanca. But it was a step up from The Swamp of MASH. The look was decidedly Indochine shabby chic.

We talked about home, sports, our girlfriends, dogs, cars, trucks, whatever! But absolutely no war stories. A handful of times, some hot shot helicopter pilot, whose job mostly entailed ferrying the Commanding General around the AO, felt compelled to share some combat derring do. This usually happened in an attempt to impress any of the Red Cross girls—the Donut Dollies—who sometimes came by. All well and good. But if anyone had a hard time complying with the no war stories policy, they were politely asked not to return. It wasn’t a lack of respect and honor for those who endured combat. But back then, it was abundantly clear that politics at 50,000 feet was the only thing standing between a whole lot of people of various nationalities and political persuasions going home to safety, or continuing to be killed and maimed. It was too far out of the ballpark–too surreal a reminder of the war’s utter madness and futility–to be sharing war stories as if there was some redeeming moral point to it all.

In these strange and troubled present days, there’s few things I miss more than gathering in a tavern to share good times, or to seek or receive moral support through the bad ones. Cocktail culture was never a part of my upbringing. But at the Hog Farm in Vietnam I found a community of soldiers who created a safe space, a reality temporarily walled off from the war. I learned a lot about who we were as young Americans from all over, and how we wound up where we were. It was a momentary fantasy of control over our fate. The Hog Farm promised everything precious that Vietnam and the war did not.

Sure, there were the letters from home, photos of Natalie, care package of cookies from my darling aunts, and the hope and promise of an eventual return back to the world—to college, to loved ones, and a “normal” life. But in real time, night to night, week to week, it was the camaraderie at the Hog Farm that ultimately served as my staff and my rod.

Nothing I would have liked better that day in Watkins Glen in 1974 than to have actually reunited with Bitch; with Head Hog. I’d have bought him a drink—his money wouldn’t be any good in my hometown. We’d have listened to some Creedence Clearwater. We’d have caught up on being several years back in the world.

And we wouldn’t have told each other any war stories.