54 years ago this day, the heartlessness of the Vietnam War came home to America: four dead, eight wounded at Kent State University in Ohio. More domestic violence would follow. The war against the war raged in a divided nation. Is it 1970 all over again?

The first time I saw the iconic 4-pronged peace sign of the 1960s, wasn’t even in the ’60s. It was around 1959, well before there was such a thing as a Vietnam War, at least a Vietnam war that Americans knew or cared about. I was barely 10 years old. The peace sign was on a placard in a newspaper photo of a Ban the Bomb nuclear disarmament protest. No long haired ’60s hippies in sight. This was a 1950s “beat” generation thing.

The mere idea of protest was revealing to me personally at the time. Is that really a thing, I wondered? Certainly not in my world. Protest? Demonstration? Rebellion against authority? No way, no how in my family or social sphere. The working, middle-class, Italian-American world that I knew then was head down, be good, don’t make waves, go along to get along, and hope the shit doesn’t come down hard on you personally. Because it will come down hard somewhere. It always did.

But things change. For my generation, when the shit came down in the form of a foreign war, the gloves came off. By the time I got to Vietnam in 1971– even there–the peace sign was ominpresent: on amulets that soldiers wore in the field, on tattoos that emblazoned their bodies, and even on unauthorized protest flags they blatantly flew in the field during military operations. There was a war against the war.

The early anti-war protests in the mid to late ’60s, focused on President Johnson’s continued escalation of the war: more and more young American men sent to Vietnam with his expansion of the military draft. Johnson wanted to get out of the Vietnam that he inherited, but he couldn’t think of any way to do it except to try and win it. His failed reach for victory was his demise, as well as an extended nightmare for the Vietnamese and our nation. “Hey hey, LBJ, how many kids did you kill today?” was the signature chant hurled in Johnson’s direction. As the draft increased, dissenters at sit ins and draft-card burning rallies cried out: “Hell no, we won’t go.”

Intellectually spawned “teach ins,” like the one at the University of Wisconsin, spread an anti-war gospel that the US had no place in Vietnam, and were cloned at other colleges. Most of the campus-based anti-war movement was agitated by new-left organizations such as the Students for Democratic Society (SDS), and the long-established pacifist War Resisters League. On Main Street, however, there was pushback. 70,000 supporters of the war marched in New York City in 1967.

Martin Luther King publicly decried the US in Vietnam in 1967, citing the war as “a blasphemy against all that America stands for.” Nearly the same time, World Heavyweight boxing champion Muhammad Ali refused induction into the US Army as a conscientious objector, saying famously, “I ain’t got no quarrel with them Viet Cong.” Ali was arrested and charged with draft evasion.

The Champ was not alone. More than 200,000 men were accused of resisting the draft illegally during the Vietnam era. And quite a few–estimates vary from 30,000 to 100,000–went elsewhere, Canada or Sweden or Mexico, to beat the draft. Soldiers too found the war extremely unpopular and walked out on it. Desertions from the Vietnam era military numbered 420,000 between 1966 and 1972. As a percentage of enlisted men, desertions averaged around five percent during the height of the war. Through all of World War II, of the 16 million who served, only 40,000 men deserted, significantly less than one percent.

But it was all below the radar for me. Those were my high school and early college days. The war and the draft were pretty far from my mind. I was white and college bound. No need to worry. My biggest concern about draft cards was making enough phony ones in my high school print shop in 1966 when my buddy Charlie and I had a budding enterprise of providing fake ID proof to underage drinkers like ourselves. Life was good.

Until it wasn’t. In 1969, when I was politely asked to take a semester off from the University of Bridgeport, I saw the handwriting on the draft board wall. Losing my student deferment placed me square in the crosshairs of the Coney Island based Selective Service office. I pleaded with my history teacher to change my grade by one letter which would be the difference between my 2S student deferment and the ranks of 1A eligibility. He stood firm saying: “This war is almost over.” He was as lousy a prognosticator as he was a historian.

My professor was conjuring the fallout from the 1968 Tet Offensive uprising in Vietnam, which put the war front and center in every living room and dining room throughout the US. American soldiers fought hand-to-hand, close-combat with Viet Cong and NVA upstarts. The American Embassy was invaded in Saigon. Following Tet, President Johnson decided not to seek re-election. And massive anti-war protests again were the rule of the day on college campuses everywhere.

Following an on-site inspection of Vietnam after Tet, CBS anchorman Walter Cronkite, often considered the “most trusted man in the US,” went on the air to declare the Vietnam war a “quagmire,” and opine that the US was helplessly caught in an unwinnable stalemate. That got the attention of middle Americans, if not the right wing hawks. It was a turning point.

In 1969, with newly elected President Nixon in office, the protests grew as did the continued escalation of the war. In October, while I was low-crawling under barbed wire, learning to shoot an M-16 automatic rifle, and doing KP for my basic training at Ft. Gordon, GA, an estimated 2 million protesters rallied and marched in “moratoriums” across the US; the largest collective anti-war demonstrations in history. The following month, the antiwar furor went international when Seymour Hersh broke the story of the My Lai massacre.

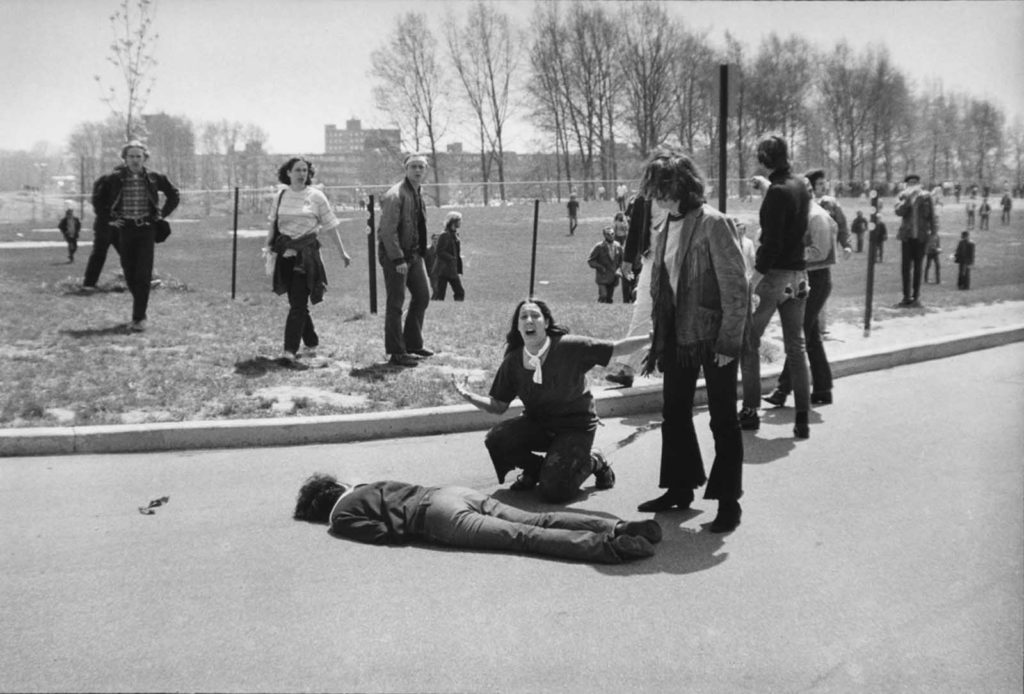

In 1970, the Vietnam war’s heartlessness came home to the USA. On May 4, 51 years ago today, we were all shocked by 13 seconds of lethal violence on the Kent State University campus. Four dead in Ohio; eight more students wounded. Shot down by bayonet-wielding National Guard troops ordered to break up a protest against President Nixon’s invasion of Cambodia. Outrage over the expansion of the war and the campus killings stirred up a lethal elixir of wider and more vociferous protests in cities and on campuses. Four million students went on strike at more than 450 colleges. Ten days after the Kent State shootings, at Jackson State College in Mississippi, police in riot gear shot and killed two persons and wounded 12. There were also counter-protests like the infamous “hard hat” rally in New York’s financial district. Blue collar construction workers took to the streets in support of Nixon and, in particular, in opposition to an anti-war protest march. There was fisticuffs for nearly 2-hours. New York City police stood by without interference in some cases. Following the Kent State shootings, a poll reported that nearly 60 percent of Americans thought the students were to blame for the carnage. Only 11 found fault with the 28 National Guardsmen who fired nearly 70 shots and hit students a football field or more away. We were a nation divided, confused and literally killing each other.

Around this time, Congress showed signs of being fed up with the war. At least, part of the legislature did. In September, 1970, Senator George McGovern of South Dakota co-sponsored an amendment to a defense department spending bill that required an end to military operations in Vietnam by year’s end, and a complete withdrawal of American forces by June of 1971. There were high hopes for this so-called “amendment to end the war.” It seemed as if, finally, there was some rational thinking in Washington. Before the vote, Senator McGovern labeled the Vietnam war as “damnable,” and, quoting parliamentarian Edmund Burke, admonished his congressional colleagues: “A conscientious man would be cautious how he dealt in blood.” But the amendment failed by a 55–39 margin. So the band played on.

In the spring of 1971, I was looking forward to getting home from Vietnam. I knew it would be to a highly charged environment when I returned. That was the year the anti-war movement went on the offensive big time. At the end of April, 500,000 people demonstrated against the Vietnam War in Washington, DC. It was the largest-ever demonstration opposing a U.S. war. Simultaneously, 150,000 people marched at a rally in San Francisco. Natalie attended the DC demonstration, driving down from New York with two of our closest friends. They parked in the city’s outskirt and then marched along with other demonstrators to the mall. The capitol was mobbed. She wrote to me in Vietnam about this adventure and I was surprised. I was very skeptical of all “group activities,” and told her so in a return letter.

Meanwhile, the springtime DC demonstrations continued. The so-called May Day Protests, which coincided with the one year anniversary of Kent State, were designed to shut down the government and commuter traffic throughout Washington. More than 7,000 protesters were arrested by police, national guard and other military troops that Nixon put on alert after getting a copy of the protest plans.

I came home in June, just when the Pentagon Papers, stolen secret defense department documents which revealed the government’s duplicity in promoting and promulgating the Vietnam War since its earliest days, were published in the New York Times and Washington Post. This caused still more furor in the anti-war movement which was swelling with middle of the road Americans every day that the war continued, and with every revelation of its corrupt implementation.

By this time, the Vietnam Veterans Against the War (VVAW) was a large and highly vocal organization, agitating for war’s end with greater sophistication than the ground roots student movements. In Detroit, VVAW organized the Winter Soldier Investigation to memorialize and publicize war crimes and atrocities committed and witnessed by line soldiers and officers alike. The three-day media event featured testimony from more than 100 Vietnam veterans from each branch of military service, as well as civilian contractors, medical personnel and academics.

John Kerry, who would later be a US Senator, the Democratic Party Presidential candidate in 2004, and eventually Secretary of State under President Obama, was a key organizer. Testifying as a leader of VVAW in Senate hearings called by Senator J. William Fulbright later that year, Kerry challenged the lawmakers: “How do you ask a man to be the last man to die in Vietnam? How do you ask a man to be the last man to die for a mistake?”

Yet the war pressed on. Looking toward his reelection campaign, Nixon’s strategy of Vietnamization meant less missions by US ground personnel, a slow reduction of forces in Vietnam, but massive bombings of targets in both North and South Vietnam and in nearby neighboring countries of Laos and Cambodia. The logistical and political support for the unstable government regime in South Vietnam continued unabated.

I was back to college, working a part time job, resuming my life with Natalie. We attended anti-war concerts and fundraisers in Central Park, and at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine that year. But my veteran status and Vietnam service was hardly front and center in my life. And the war dragged on despite the best efforts of those who would have it ended. In 1972, Jane Fonda visited Hanoi to publicize the devastating bombing that was conducted there by the US Air Force and Navy. In August, at the Republican National Convention, crippled Vietnam veteran Ron Kovic–famously played by Tom Cruise in the Born on the 4th of July movie–rolled his wheelchair down the main aisle as Nixon began his re-nomination acceptance speech shouting, “Stop the bombing! Stop the bombing!”

Nixon’s “four more years” campaign scored a landslide victory over the Democratic peace candidate, George McGovern, that year. The American electorate remained as reluctant as Nixon to leave Vietnam without a victory, even though no one had any clear picture what a win in Vietnam could possibly look like after more than 50,000 US war dead. On January 28, 1973, after callous, death-dealing Christmas bombings of Hanoi and the rest of North Vietnam, a cease fire took place. The last remaining US combat troops withdrew from Vietnam in March.

Personally, I don’t have a dog in the fight going on mercilessly in the Mideast right now. But I do have an unfathomable ache in my hear for all the death and destruction, mayhem and terror, sorrow and pity that defines the moment by moment life of those enduring it in real time. And in Ukraine. And elsewhere. Put the politics aside–the right, the wrong, who did what to whom–and it still shakes out like it did in 1970. War is not the answer.

The demonstrations leading up to 1970 and beyond, had a material effect on the end of the Vietnam War. If government leaders around the world today can’t find the moral courage to knock off the shit, then I raise a fist in support of the student demonstrators who have the mettle to stand and deliver the message: “ENOUGH!”

Power to the protest.