Imagine strolling past the Boston home of Paul Revere, and not having a clue. Not likely, right? But in Ho Chi Minh City, revolutionary history is unseen and unheeded every day at an unassuming noodle shop that is the site of a Vietnam War story extraordinaire

I had survived nearly a year in Vietnam during the war with hardly a scratch. So on my return there in 2018, it seemed over the top to be risking life and limb just to reach a hole-in-the-wall noodle shop not dissimilar from so many hundreds of others in the bustling heart of the city I once knew as Saigon. The madcap midday ballet of motorbikes, pedicabs and street-vendor carts veering chaotically on narrow Ly Chinh Thang Street gave me pause. But I was hungry, and my guide and translator, Kevin Huynh, beckoned me forward with a sly grin. So I dodged through the noisy traffic, crossed the street, and began to salivate when I whiffed the tangy aroma of chicken and beef broths steaming from the restaurant’s simmering cauldrons.

But we didn’t take a seat in the fragrant, tile-walled dining area. Instead, Kevin coaxed me to follow him up a narrow, rear staircase. We climbed past some cluttered living quarters. The top floor was a cool, shaded sitting room. Awaiting us was Mr. Ngo Van Lap, a serious looking fellow with erect posture and a punctilious military buzz cut. He was 10 years my junior but looked ancient in his unsmiling silence. Without rising, he gestured for me to join him on a leather couch in front of a large round coffee table, which was arrayed with books, documents and old photographs. I realized we were not there for lunch.

I had come to Mr. Lap’s residence, atop Pho Binh restaurant. This was also a one-room museum, dedicated to a remarkable, yet little-known tale of the so-called Communist Tet Offensive of the Vietnam War. Over the next two hours, Mr. Lap walked me through a war story so fantastic and so fateful that, at first, I had trouble believing it. Imagine strolling past the home of Paul Revere in Boston without having a clue to its significance. That’s the level of revolutionary history which is hidden in plain sight at 7 Ly Chinh Thang Street. The role of Pho Binh restaurant—and Mr. Lap’s family—during the 1968 Battle of Saigon, is as epic in Vietnam as is the midnight ride of our colonial patriot in 1775 Massachusetts.

Despite its modesty, decades earlier, Mr. Lap’s restaurant was a key staging ground of the infamous Tet uprising. Tet, the Lunar New Year festival celebrated throughout Southeast Asia, is Christmas, New Year’s Eve and Easter all rolled into one week-long, late winter holiday. It’s a forward looking celebration of spring’s renewal, and a reminiscence of the past year. Homes, businesses and public spaces get all gussied up. Friends and family travel to their hometowns from near and abroad. Tet commemorations include street pageants, elaborate meals, and gift giving. There’s parties and prayers, rituals and ceremonies.

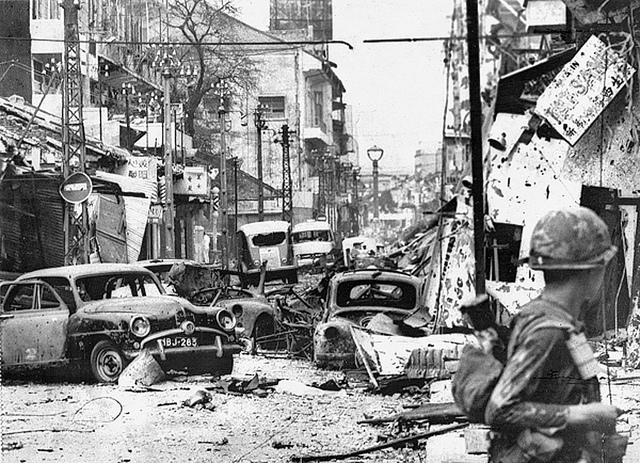

In 1968, Tet was all that, and so much more in Vietnam. The war was officially put on hold. A temporary holiday ceasefire was agreed upon, providing the opportunity for Vietnamese forces on both sides to take leave and be with family. But Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Army forces had something else in mind. After months of meticulous and covert planning, they rose up in sneak attacks across hundreds of South Vietnam cities, towns, and hamlets. Bloody battles and political assassinations continued for days. Thousands died; hundreds were kidnapped, murdered or both. Tet 1968 was the opening salvo of what would become the deadliest year of the entire Vietnam War.

Eventually, the Tet Offensive was quelled by overwhelming US and South Vietnamese military force. But not before the communists made their bloody point. The war to liberate the South and unite Vietnam was far from over. Indeed, the Tet uprising became the enduring symbol that the struggle for independence would never be abandoned, no matter the odds or the cost. From that time forward, the American public, its elected representatives, and the national media lost their taste for the Vietnam War. Hope for a definitive American win, or any conclusion to the war short of withdrawal, fizzled. It took five more violent years for US troops to leave Vietnam; more than 30,000 young Americans would die in the war following Tet. It would be eight more years before peace concluded. And ground zero for the beginning of this drawn out slog to the war’s end, I was learning from Mr. Lap on an empty stomach some 50 years later, was essentially right there at the Pho Binh noodle shop.

Mr. Lap was not the first person I had met from the opposing ranks during my return trip to Vietnam. In the north, I was introduced to former NVA soldiers who, like me, had been drafted and sent thousands of miles away from the comfort of friends, family and loved ones. Meeting decades after the fact, we recognized each other as having shared the same fears and sacrifices. We knew we were the lucky survivors of a tragic chapter in history. We mourned identically, compatriots far less fortunate than ourselves. That there can be more kinship than animosity between Americans and Vietnamese is often a phenomenal surprise to non-veterans. I wasn’t sure what my reaction would be before I experienced it. My only reference point was a 1960s TV show episode that I vividly remember, about an American World War II veteran who suffered violent flashbacks to his fighting in the South Pacific during an encounter with a young Japanese American decades after the war. In my case, there was nothing of the sort. It seemed perfectly logical and natural to greet my Vietnamese counterparts more as distant brothers than as old enemies.

During the war, of course, Mr. Lap was a mere school boy. But he was part of the communist cause, even as he waited on tables for his father, Mr. Ngo Toai, who owned the restaurant. For years, as an officer of the undercover F100 Viet Cong cell, Mr. Toai smuggled weapons through his restaurant. Vietnamese and American diners slurped noodle soup on the floors above his basement during the war, and were none the wiser to the arms and ammunition secreted literally beneath their feet.

Weeks before the 1968 Tet attacks, Viet Cong fighters began secretly infiltrating Saigon. They disappeared into numerous staging points such as Pho Binh. The young Mr. Lap was trained to recognize a Viet Cong cohort when someone ordered an odd sounding dish not on the restaurant’s menu. With this coded message, he sent the would-be diners to the same rear staircase I had just climbed. An attic became temporary barracks for more than 100 Viet Cong commandos.

The offensive kicked off in the wee small hours of January 31, under the cover of fireworks celebrations on the first night of Tet. The fighters holed up in Mr. Toai’s shop targeted the Prime Minister’s palace, the Saigon radio station, and the US Embassy, which they breached. According to Mr. Lap, only seventeen of the Pho Binh fighters survived. Most were quickly arrested and imprisoned. At least two were executed on the spot by frustrated and furious South Vietnamese military police.

The Tet uprising was a propaganda victory of the highest order for the Viet Cong and North Vietnam. It was a strategic turning point in the war. But it also was very costly. As many as 60,000 NVA and VC fighters were killed in the battles. That’s as many as the total US military lost during the entire war. The F100 Viet Cong cell was virtually decimated in three days. Mr. Toai was arrested and imprisoned on Con Dao, the Devil’s Island of Vietnam war prisons, infamous for its torturous tiger cages. He was released in 1973 in a prisoner exchange, and passed away in 2006 at his apartment, right there where I sat with his son, in awe.

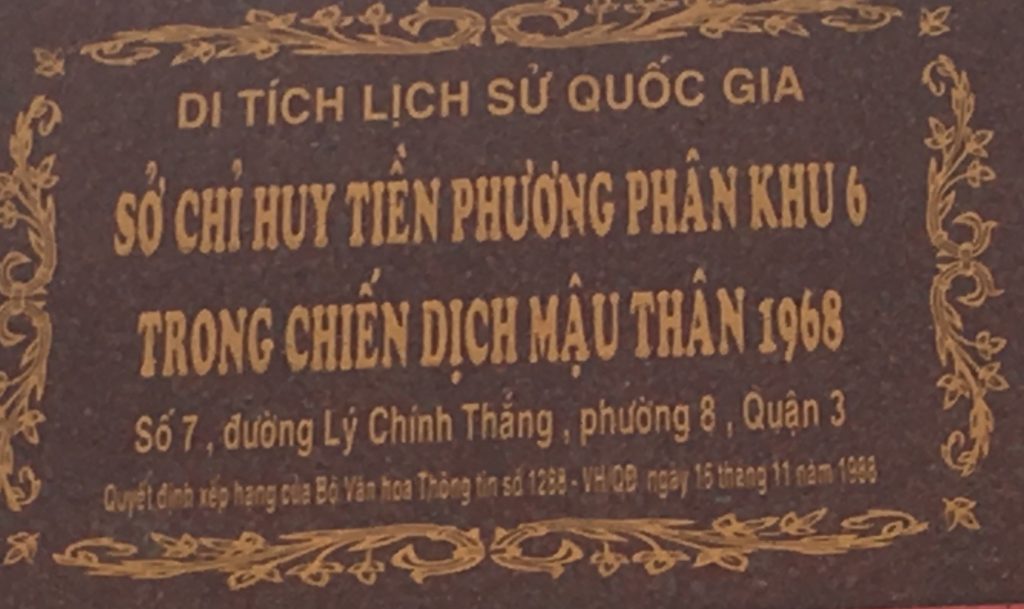

The centerpiece of the Tet holiday this year in modern Ho Chi Minh City is Memorial Park where the statue of Ho Chi Minh —“Uncle” as he is called—looks out over a vast downtown pedestrian mall. It will be festooned with potted apricot, mandarin and peach blossom trees and millions of brightly colored flowers. Chic Vietnamese women will promenade in silky embroidered Ao Dai dresses, and children will play with LED-lit pinwheels and mechanical Year-Of-The-Cat toys. Meanwhile, a short walk away, the beef and chicken pho at 7 Ly Chinh Thang Street will continue to be ladled out as inconspicuously as ever. And Mr. Lap, sitting beneath a wall plaque that proclaims it a National Historical Landmark, awaits any visitors who care to learn how Pho Binh is a noodle shop extraordinarily different than any other.

Great article. Love the flower power

It really is something to see. I’ll send you some real time pix from last year and this that I received from some friends in Saigon.

Who knew? Not us! Good story, Fred. History needs to be written.

I now know what was meant by the Tet offensive. Great article

Bravo, Fredo!

Or should I say Xuất sắc!

So much more to tell on the political side–both Vietnamese and American. Military experts to this day maintain Tet ’68 was a watershed moment when the tide turned against the communists and had the South and the US pressed its advantage aggressively, the outcome of the war would have been totally different. For the communists, it was a bitter defeat militarily, but also their main strategic objective of having the citizenry AND the rank and file military of the South Vietnam rise up to “throw off the yolk of American imperialists and the puppet government of Saigon” simply did not materialize. What no one expected was the querulous media reaction to the offensive, and the change in public opinion that resulted. Faced with the horror of live TV coverage and graphic battle photos, Congress AND Johnson lost their will to support the military’s call for increased troops and actions. The US, in short, blinked. IMHO, however, even if the US had doubled down with the military option, the VC and the North Vietnamese government would have never given up. Rather, the country would have been ravaged and pillaged and its culture destroyed even more than what eventually occurred.The decade long Vietnam War could have easily stretched another 10 years or more. A lesson, unfortunately, not yet learned, vis a vis Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, etc. Unfortunately, not enough of our policy makers and leaders know or understand history.

Fred,

I loved this story in particular. I really didn’t understand the Tet Offensive before reading your account of those awful days in 1968. But your writing style is so engaging- it brings me there with you, makes the people in your story real and human. It’s a wonderful gift you have for inclusive storytelling.

Bravo my friend.

Jim Riordan

Thanks Jim. There’s many points of view. Military and foreign policy wonks to this day debate the many facets of this event and its outcome. I’ve just tried to report what I discovered in my research and my experience. The little known story of this little noodle shop was enlightening. I’m thankful to my guide Kevin Huynh (that’s him in the opening photo), for leading me there.

After 9 trips to Vietnam from Hawai’i I can still learn something new about this wonderful country. Thanks.

An aside: 1st husband flew F105snout of Thakli in ‘67-68.

At almost the same time (1966) my present husband of 38 years was a Marine radio operator based out of Chu Lai..

Excellent piece..Fred..

Reading before the Stupid Bowl, Phil? I am so f***ing impressed. Must be that good Florida air! Cheers.

Dear Sir

I am a long time friend of Kháng, I have for some years working with him on Tours to Vietnam, I too was in the Military and served in our last Colonial war Aden 1967.

I am a great admirer of 1st Air Cav.

Please bookmark my pages

Easternhorizonstravel.com, all the links are there.