The onion-skin transcript of my Army court martial is barely twelve pages long. Granted, in the annals of military justice my alleged infraction was not on par with, say, the Caine Mutiny. But neither was the charge — disobeying a lawful order — a trivial matter.

Considering that in the minds of some, it was the root cause of my assignment to Vietnam, the affair as recorded for posterity does seem kind of, in a word, thin. Still, there it is; on the pale blue Department of Defense, Form DD491 cover sheet: “Summarized Record of Trial by Special Court Martial, 13 July, 1970.” This was the case of the now-you-see-them, now-you-don’t necklace of beads worn by me, PFC Fred Abatemarco of the 13th PysOps Battalion, 2nd Psychological Operations Group, Fort Bragg, NC.

My father was virtually certain this Court Martial for wearing so-called love beads was the main reason—if not the sole one—I got sent to Vietnam with less than a year left in my Army enlistment. Mind you, it was somewhat unusual to send personnel to the war with less than the full 365 days tour of service available–but not unheard of. Mid-1970 was a weird period for the war. President Nixon was desperately trying to wind things down and bring troops home. Replacements were being made head for head, job for job, and not on the full regimental or brigade scale that was the norm through the early days of the war. If the Army through it needed one more 71Q20 Information Specialist, it may well have been a random selection that found me. Even if I’d have only about 10 months left to serve when I got there.

But you couldn’t convince my Dad of that. Indeed, that I was found not guilty—fully exonerated in today’s parlance—only fueled his certainty. If the Army couldn’t screw me one way, he felt, they found another way: an all expenses paid trip to the war in Southeast Asia. And in his mind, it would have been just punishment for my impudence. My dad leaned decidedly hawkish on the scale of war or peace in Vietnam. And when it came to “make love, not war” sympathies, he was most definitely what you’d call a straight arrow. “Beatnik bastards” was his often muttered term for war protestors. When hard hat construction workers set upon peace marchers in New York’s financial district right around the time of my travails, my dad was rooting for the attackers.

Maybe he was right about the cause and effect of my court martial. I have complete faith that I’ll never know one way or another if that’s what got me to Vietnam. I don’t really care now because it doesn’t really matter, and I didn’t care then because I was too headstrong and rebellious to have considered the consequences. I’m not a Libra for nothing. I sought justice.

The incident that triggered my legal military woes occurred at 735am on 23 April,1970, as I stood with the rest of my platoon for the daily morning inspection. On that warm spring day, in front of our modern brick barracks, Specialist E-7 Laurence Guay—the non-commissioned officer who was in charge of my platoon — made a special point of announcing that he would no longer tolerate “civilian trinkets with the duty uniform.”

Our roll call formations typically lasted all of about 15 minutes. Specialist Guay walked through the ranks checking for polished boots, missing buttons, tucked in fatigue shirts. You know, all those vital war-winning characteristics so important for a typewriter-wielding soldier. Typically, the fatigue-shirt collar button is undone, and the undergarment tee shirt exposed. That’s where Guay says he saw my multi-colored necklace of beads. “They were hanging about an inch below his neck,” he testified. Guay told the court he gave me a lawful order to remove the beads immediately. When he found out I was still wearing them later that morning, he marched me to see the “Old Man”—that’s Army-lifer speak for the officer in charge—and made a formal report that I had disobeyed his order.

What’s the deal with the beads, you wonder? They were simply one of the many ways I tried to retain some type of individuality amid all the mind numbing conformity of Army life. I wasn’t protesting the war. I simply was trying to hold onto some sense of my civilian self.

Th beads became something of a cottage industry for me during those mostly non-eventful days of permanent party status at Ft. Bragg, NC. On weekend trips to New York, I’d pop into head shops and funky clothing and accessories stores like Azuma, to stock up on the tiny plastic beads. Back at the barracks, in my off hours, I’d string them and sell them to the guys for a couple of bucks each as necklaces or bracelets. Sometimes, I’d even embroider them on their jeans in simple patterns, like a horoscope sign. That usually cost more.

So the fact that many many of my platoon mates were wearing beads around their necks and around their wrists, made me indignant that Specialist Guay had a bug up his ass about me in particular. I know that was true because one of my other pastimes was pulling pranks with my bunkmates designed to make him bonkers any chance we got.

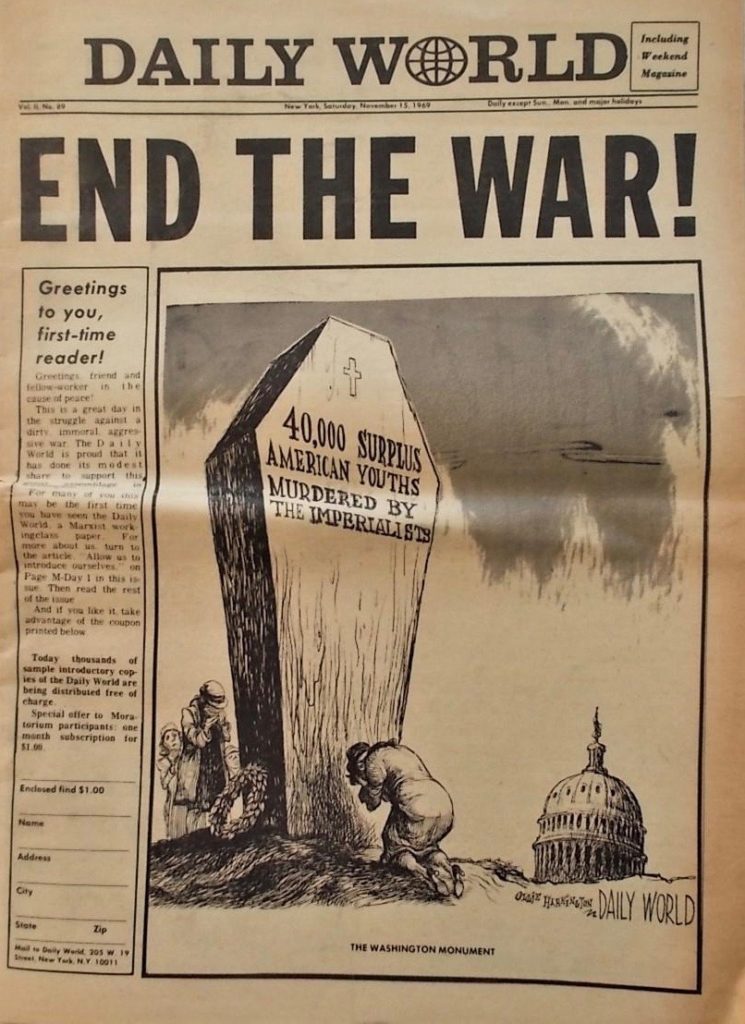

Like the time we decided to set up an unofficial lending library in our barracks. One of the periodicals we offered was the “Daily World,” the official newspaper of the American Communist Party. Specialist Guay was one of those gung-ho, my country right or wrong, uber patriots whose world view didn’t extend past the stripes on his uniform sleeve. He was USA all the way, though born in fact, somewhere in Alberta, Canada. We threatened to bring down the wrath of our First Amendment, Freedom of the Press rights, if he dared mess with our library.

Then there was the time we brought a live tree into the barracks. A fairly young sapling had been run down in the parking lot by a soldier who had one too many at one of Fayetteville’s sleazy strip-joint bars off post. My buddies and I decided to “rescue” the toppled tree by “repotting” it in a full size trash pail. Filled with dirt, soil, and freshly watered, we hauled the trash-can tree inside and awaited Specialist Guay’s jaw-dropping reaction at the next day’s barracks inspection. Our botanical do-gooder story saved us from disciplinary action, but the tree had to go. Specialist Guay was starting to catch on he was being played.

It couldn’t be more obvious, in fact, than the time four of us decided to become blondes. We had just spent a very depressing weekend day off at the Chapel Hill campus of the University of North Carolina. Pretty girls and handsome guys—all with long flowing hair only made us feel more out of sorts than usual. No matter how flared were our bell bottom jeans, we could hardly mix in with the students with our close cropped buzz cuts. We returned to base lonely and dejected. But then Ed Ossa, the most imaginative of my mischievous Fort Bragg coterie had a brain storm: “If we can’t grow our hair, let’s dye it!” So at the Post PX, we picked up their entire inventory of a color treatment called “Summer Blonde,” and applied it every day. Within a week, we evolved into towheaded wonders. Specialist Guay staggered with disbelief.

So it was a real “Gotcha!” moment for Guay when he had me standing before my company commander, officially charged with violation of Article 92 of the Uniform Code of Military Justice for allegedly not complying with Army Regulation 670-5 which specifies the proper Army uniform and insignias.

This didn’t have to be that big a deal. The Army typically deals with minor infractions against its rules with a procedure called “Article 15.” Essentially, you admit your guilt and get punished with a slap on the wrist ranging from extra duty, or loss of privileges, a small fine, to various combinations of the same. Sign the sheet, take your medicine, proceed with your life. No biggie.

But there were two very important reasons why I would in no way agree to an Article 15. First of all, as far as I was concerned, I had a perfect right to wear the beads—as much as any crucifix of Jesus, Star of David or fist of black power wearing devotee did to their amulets. And I didn’t see Specialist Guay calling down any of these “civilian trinkets.” Perhaps even more important, an Article 15 would more than likely restrict me to the base and that would be intolerable because most weekends, I went through very elaborate efforts to get home to New York to see Natalie.

I decided to stand up to the man at a court martial where I could defend myself. It was my right to do so, and my refusal to sign the Article 15 kicked the wheels of so-called military justice into neutral for the time being. Life at Ft. Bragg continued as normal. I did my job each day, had weekends off, and there were no further confrontations with Specialist Guay or any of my other superiors. I kept my love beads well out of sight during duty hours.

A few weeks later, I was summoned to see Major Kirkpatrick, a senior officer from a totally different unit. I relished the opportunity to leave my office for this appointment. It would give me a chance to “ghost”—basically fuck off—for the entire rest of the day. At Kirkpatrick’s office, however, I was confronted by yet another decision. “This is your summary Court Martial, the Major announced when I was seated in front of his desk. “Wha?,” I puzzled. “Your Summary Court Martial,” he repeated. The Major went on to explain that right then, right there in his office, mano et mano, the incident in question would be reviewed and adjudicated by him. He had Specialist Guay’s written statement, the charge sheet, and he would hear my side of the story. No witnesses, no jury, no defense counsel.

No way.

I demanded a full trial for my day in court. I had been working with an attorney from the Army’s Judge Advocate Group and felt certain I had a compelling case if I could get a chance to present it properly. The Major cautioned me: “You go before a full Special Court Martial the stakes get much, much higher. You face loss of rank, a dishonorable discharge, jail time—any or all of the above.”

He wasn’t going to scare me. At least, I wouldn’t let him think so. This was hardball.

This decision led—three months after the original incident—to a stuffy, humid conference room on a stifling mid summer day. There, Major Charles Humphries, a Vietnam combat veteran presided as my sole judge and jury. There was a prosecuting attorney and assistant, my two-lawyer defense team, witnesses for both sides. I, the accused, and Specialist Guay, the accuser. No spectators.

Major Humphries was unabashedly bored to tears by the three-hour proceedings. He chain smoked unfiltered Pall Mall cigarettes, blowing smoke rings through the dirty window screen, leaning back in a squeaky desk chair, his feet propped up on the scarred painted wooden table that passed for the court bench.

I had been advised by my JAG defense attorney, Captain George W. Clarke, that my best strategy was to waive a full jury. Unlike the fantasy of civilian justice, a military jury would most certainly NOT consist of my peers. Instead, it would be a half dozen lieutenants and captains: “Junior grade officers whose greatest military career satisfaction right now would be teaching a rebellious draftee like you a lesson you won’t forget,” advised my attorney. Trial by judge was a very easy decision to make.

The final decision in the chain was, of course, made by Major Humphries. The testimony of Specialist Guay was inconsistent and unconvincing compared with his written statement. Defense witnesses contradicted Guay’s claim that he told me to remove the beads. The lasting impression was that he told me “he did not want to see the beads,” according to witnesses who testified that the beads were no longer in sight after the formation.

Really, it wasn’t even a contest. Had the trial been a prize fight, the ref would have stopped it in the first round. Minutes after the closing statements the judge summarily shooed us from his overheated, nicotine saturated courtroom with a verdict of “Not guilty, case dismissed.” My bunkmates and I celebrated that night with a victory banner and Kool-Aid. I flaunted my triumph to family, friend and foe. I fought the power and won.

Three months later, I received my orders to report to Vietnam.

Picture of you as a blond, please.

Wow, the price of victory… your Dad may have been right about that much!

OMG Fred. I had no idea! You a blond? AZUMA!

Reading this now is hilarious, but if (like Dad thought) this was your ticket to Vietnam back then, not so funny. LOVE YOU!

From one 71Q20 to another, that is one bitchin tale! I wish we could share Army stories some time. Thank God you returned safe and sound from the hellhole.

How funny. I love the saga and makes my 15 yr old rebellious grandson seem soooo normal. What a handful you must have been but how would you look with red hair?

i guess i take after you. im talking about the beading and embroidery. did you think i meant the distaste for authority?

You funniest posting yet! While I was reading the image of those colored beads of the time came to mind, but then there they were in a photograph. They indeed should make one of those great courtroom movies based on the court marshall of Fred.

No veterans here to hug, but it was a beautiful sunny day here in Lindon and we celebrate what i think is very beautifully termed, Remembrance Day. The ceremony before the Queen, royal family, leaders of all parties and past prime ministers, representatives of all Commonwealth countries, .

crown dependencies and territories, and thousands of veterans until recently including The Great War, at the Cenotaph laying wreaths…The losses in the two world wars were so great for the British that even this long afterwards it is deeply remembered and those lost honored. We all were the poppy for the two weeks leading up to Remembrance Day.

Carla: If only one existed! But who knows, if I can track down Ed Ossa…..

Thanks, Bob. Losses, no matter when or where, are long remembered. If only we could learn from them and stop repeating the same folly of war.

Diane–Yes and yes! I am proud and pleased to have you as my progeny.

This is great, Fred. I agree that the Army got even with you by sending you to Vietnam. It was a time it was and you have captured it. Congratulations!

Glad you won the case, Fred, & that you did not have to resort to a Tommy Lazaro tactic to get even. BTW, your Dad was absolutely right on!

Felix: So there were worse folks than me in the military!

Johanna—from a military family, I know you can relate!

BEATNIK BASTARDS????..

Loved it..

So that’s what was going on in Fort Bragg all those years ago? I would love to hear the perspectives of Major Humphries and Specialist Guay on the matter. And I wonder what color hair Ed Ossa has today? (I too would love to see the towheaded Fred)

This story is so characteristic of you and of course so very well written! I think I still have my beads…

Love reading your posts.

Loved this story Fred. My husband read it as well. He was in the national guard at the time so he could relate. Thanks for the story and I miss you

I wore my love beads under my Red Cross uniform after I got back. I can’t remember if I was chastised for them but I do remember trying to keep them out of sight

Holly–Miss you too. See you for holiday cocktails. Give me the heads up when it happens.

That line was DEF for you, Avuncular Phil!

Kathy–are you suggesting I did not represent them honestly and fairly? I bristle at the mere idea!

Nancy–cause you were a “by the book” kind of gal, n’est-ce pas?

The Fred we grew up with and grew to love and still breaking balls after all these years.

Doc—Would you have me any other way?

I was led to believe there were two types of levy for Viet Nam:

1. You were levied by name, probably based on MOS;

2. Your unit was told to send X number of men, a chance for the commander to “clean house.” Sounds like you were in the latter.

Great story. Glad to know there really was some ” J ” in the UCMJ.

Fascinating, Fred! Not entirely different from my service experience as it turns out. Some minor differences. First off, I was in ROTC. In the band for four years of college. As a consequence, I didn’t learn the manual of arms or any of that military stuff. At summer camp, the Captain said he was not in the business of handing out commissions, but guess what? He was. I would sing my two favorite Tom Leher songs: It Makes a Fellow Proud to be a Soldier and So Long Mom, I’m off the Drop the Bomb, while marching to the ranges. Captain Huber told me not to do it. I somehow forgot what he said. But, at the end of the camp, as bad as I was, as much as I ignored the good captain, I was commissioned by General Light-at the End of the Tunnel himself, William Westmoreland.

At Engineer basic in 1970 ( the LAST class that was not sloughed into the National Guard) they offered us this deal called Volunteer Indefinite: sign up for an extra year and get more time-consuming instructional courses and a full first year assignment of your choice. Perhaps, by the second year of the service the war will be over! I, and three others from my school–with the help of girlfriends and wives, were among the few who resisted signing up for VI. NONE of the who signed up for it went to RVN. We four got our orders on the same day.)

Although my MOS was Combat Engineer ( 1331) I talked my way into the Americal Artillery information officer position. Early in my tour, I was assigned to be witnessing officer of the destruction of millions of half dollar-, quarter- and nickel-sized slugs that had been used in slot machines throughout Viet Nam. The machines had been there since the war began, but they were banned in February of 1971. While it was easy to round up the machines and send them back to the states, the slugs (which you would purchase with MPC to use in the slots) were simply unminted blanks that could be used in any vending machine and were kept in RVN for disposal. My job was to witness to the destruction of all the slugs that had been in the Americal Division.

The were melted down using thermite grenades. Bags upons bags of slugs. All melted. Except eight months later, they found more slugs. How would I know there were more slugs? Since I had signed off as Witnessing Officer, the JAG officer recommended that I be court marshalled for dereliction of duty. How did I get out of that? ( A typhoon came along )

Fred–I’d like to say that is the most bizarre tale of Army madness that I ever heard. But, weird as it is, it isn’t the weirdest!

Very interesting, Michael. I didn’t know that and will look into it further. Thanks.