Chu Lai was my home away from home during the Vietnam War. Though you likely never heard of it, Chu Lai was much much more. What happened in and around Chu Lai turned out to be emblematic of the misery and tragedy of the entire war.

In some respects, Chu Lai is where the Vietnam War began and ended for the United States. The first major battle involving US troops took place there. The last major attack on a US field base was the surprise attack at Firebase MaryAnn—a Chu Lai outpost. And the air support for the final major operation of US forces in Vietnam–Operation Lam Son 719–was flown by Americal Division units from Chu Lai.

What happened in and around Chu Lai turned out to be emblematic. Virtually all the misery and tragedy that eventually turned the hearts and minds of Americans against the war, visited upon or germinated from Chu Lai. Civilian massacres. Rampant drug use. Fragging murders of officers by their own soldiers. Agent Orange poisoning of the countryside. Lies and deceit by the war runners. Chu Lai had it all. And an ocean view to boot.

The road there was a long one for me the first time around, in 1970. I dropped out of college in ’68 and lost my student deferment from the draft. Selective Service swooped me up in 1969, right before the national lottery. After basic training, permanent party status at a research desk at Fort Bragg, NC and an Army court martial worthy of Catch-22 (full disclosure: it involved love beads and I was acquitted of the charge), I wound up in Chu Lai with hardly 12 months left of active duty.

And yet, my return to Chu Lai in 2018, was perhaps even more convoluted. An entire lifetime intervened. Decades of marriage, births, deaths, children raised to adulthood, a heart attack survived, a rewarding career nurtured and concluded. Like so many others, I put Vietnam in the rearview mirror when I returned home. More precisely “Fred in Vietnam” got tucked away, out of sight and mind.

But in the last couple of years, Vietnam became an itch that I could not resist scratching. A top priority for my return was to “put boots on the ground” once again where I had been stationed during the war: The sprawling seaside base camp of the infamous 23rd Infantry Americal Division, Chu Lai. So on a hot and steamy March morning, exactly, 46 years and 9 months after I left the war, I found myself back on the beach at Chu Lai, looking for my past. What I found there was basically nothing. Physically, metaphysically, or otherwise.

Maybe that shouldn’t be such a surprise because Chu Lai, in the most technical sense, didn’t really exist until it was conjured from the ether, as were so many other fabrications woven to become the lore that we call The Vietnam War.

True, Chu Lai was among the largest of any of the US military installations in Vietnam. Before the war was done, it would be home to the largest Army division in Vietnam, a Navy Swift Boat port, and a major Marines fighter-bomber airbase. However, before the American military arrived in 1965, the Batangan Peninsula was a sleepy, boggy isthmus, hanging off the central coast of Vietnam like a stubby finger.

The words “Chu Lai” were nonsense; not even Vietnamese. Rather, they are a Mandarin Chinese abbreviation for the family name of US Marine General Victor Krulak. It was he who selected the area around Dung Quat Bay for construction of an air field and naval base as Lyndon Johnson shifted the US military build up into high gear. When the General learned the area had no name associated with it on the maps of the day, he rechristened the area in his own honor.

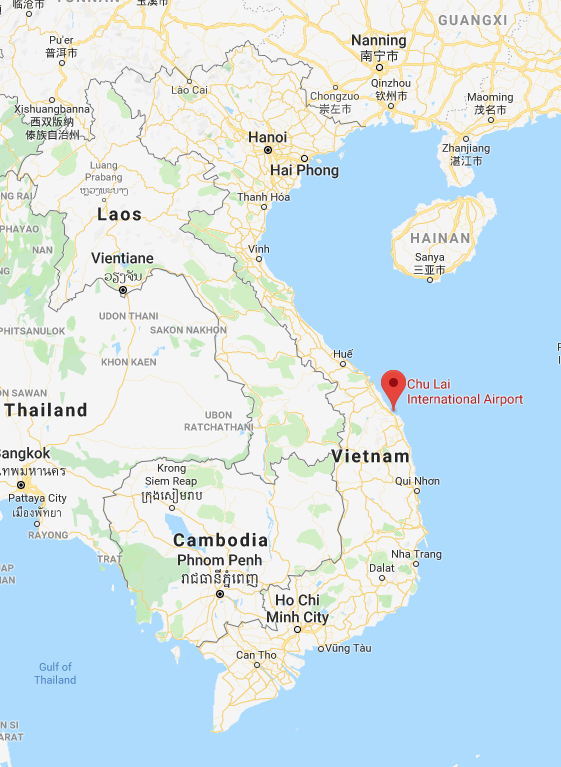

Chu Lai is about equidistant—some 900 kilometers—from Saigon in the south and Hanoi in the North. Tiny hamlets dotted its landscape back then, populated by rice farmers or fishermen. From these came our base workers of hootch maids, barbers, launderers and massage parlor prostitutes. Tam Ky, essentially a dusty ramshackle village where we’d go to buy dope and watermelons during the war, was the closest thing to a nearby city—some 30 clicks up the main road. Another 60 kilometers north, a 30 minute chopper ride, sits the major seaport, international airport and regional capital, DaNang.

Chu Lai occurs where the landmass of central Vietnam begins to widen from its narrow corridor between the South China Sea and the Annamite Mountains. The mountains form a natural border with Laos to the west, and the Mekong River Valley to the south. Chu Lai’s lowlands, coastal plains and rice paddies intercept the sea, forming a lagoon sheltered by grassy dunes, windy bluffs, rocky beaches and sandy coves.

The area takes its place among some of the most picturesque beaches of Vietnam’s entire 2,000 mile coastline. In 1970, it certainly was the most beautiful and exotic place I had ever seen, though that was a pretty low bar. I had never been on a plane until the day I was inducted into the Army. Until then, I had barely been beyond the five boroughs of New York, or Long Island.

In Chu Lai, the air was always moist with the sea. I could practically taste the briny mildew on my fatigues. Excruciatingly hot inland during the dry season, it could be bone-chillingly cold when the mountains held the rain clouds in. There would be days-long deluges during the monsoon season. Nonetheless, I never got over the area’s powerful beauty. For sure, that wasn’t the draw for the US military. Central Vietnam was a hotbed of revolutionary activity in the 1960’s. Serious “injun country” in the crude parlance of Vietnam era slang; and the terrain was ideal for land, air and marine facilities.

For my return, I connected with Cau Nguyen Huu, a former translator for one of our Infantry brigades, to serve as my guide. And the first place he took me was up a 150 foot hill-climb to a towering memorial, erected in honor of a battle that the Viet Cong instigated as a welcome to the US Marines in May of 1965. The so-called Battle of Ba Gia commenced barely two weeks after the Marines got to Chu Lai. Though little known, this rout of the South Vietnamese forces in the area and their US military advisors, was instrumental in convinced President Johnson the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) couldn’t go it alone.

Three months later, with the first wave of Marines firmly established in country, the Americanization of the war hit full stride. The US went on the offensive in Chu Lai with “Operation Starlite”. This was a sustained, bloody and controversial week-long battle. It was the debut of air mobile helicopter assaults that became ubiquitous throughout the rest of the war. Almost 50 US Marines died, and more than 200 were wounded. The US reported more than 600 Vietcong killed in action. Two US soldiers in the operation received the Medal of Honor, one of whom died of his wounds. The battle was the first major fight by U.S. forces against a sizable Viet Cong unit. Despite US claims of success, the Viet Cong announcing that they had inflicted 900 American casualties, destroyed 22 armored vehicles, and downed 13 helicopters.

A highly respected news reporter documented the deadly ambush and destruction of a US armored convoy during Operation Starlite, which was never officially acknowledged by military officials. The convoy was first bogged down and crippled by the rice paddy terrain, which was unfamiliar to US soldiers. Then the unit was decimated by an overwhelming and unrelenting enemy siege. When shown photographic proof of the event, the commander who denied that it happened relented by saying: “I was misinformed”. If ever there was a tone deaf quote of Bogie’s Rick Blaine from Casablanca, that was it.

After we left the war memorial, Cau directed us past what had been the main gate of my former base. It’s a Vietnamese Army post now, obviously off limits to me and all other civilians. Most of the sprawling facility has been subsumed by nature over nearly half a century. Cau still knows the area intimately. We took an unmarked road past the base’s old airstrip. Pretty soon we were high stepping through scrub brush and hacking through gnarly vines on an overgrown bluff to get within earshot of rock-smacking waves on the beach below.

The bluff where the 91st Evacuation Hospital stood is still there, but it is silent and deserted now. All the plank wood walls, corrugated tin roofs and every other piece of salvage and scrap was long ago carted off to become the stuff of daily living for the residents of An Tan and other nearby hamlets. There’s no trace of the parade grounds where our division hootches were clustered, or the amphitheater where Bob Hope and Raquel Welch performed. The hill where the Donut Dollies and the base commander had their air conditioned trailers is a mere memory. The base I knew is buried and forgotten under five decades of post-war foliage.

There’s a handful of thatched roof restaurants right above the high tide mark where our base’s Combat Training Center used to be. Cau leads us there and we feast on a seafood lunch among the locals: Fresh oysters and clams roasted with fish sauce, chilies and peanuts. A whole grilled fish, pungent with garlic, scallions, ginger and lime. Summer rolls, tiny dove eggs, cold beers. I wade in the surf and squint my eyes to recall walking, driving, patrolling these shores. With all my might, I try to reawaken my infatuation with Chu Lai’s lush rural beauty; the fabulous seascapes; the pastoral rice paddies.

In 1983, the Chu Lai area officially became the Núi Thành District, much as the Vietnamese originally called the region. Today, the district is a busy, fast developing, industrial area of the modern Vietnam. It boasts a world class seaport for shipping. It’s home to the country’s only privately financed automotive manufacturing plant, a joint venture with Korea’s Kia Motors, building cars, trucks, buses for domestic use and export. The former military air base has found a new life as the Chu Lai International Airport, the largest in the country and rapidly becoming one of the busiest. Industrial parks abound. The only thing still to come are the tourists.

At the end of November, 1971, months after I departed, a powerful typhoon came ashore at Chu Lai, virtually leveling the base. The Army decided that was Heaven’s way of saying “enough.” The Americal Division abandoned Chu Lai, departed Vietnam, and officially deactivated in Fort Lewis, WA., ironically, the original point of my departure for Vietnam. The Chu Lai I had been holding onto for decades, had virtually evaporated mere months after I left. It took my return 47 years later to wipe it from my mind. My Chu Lai, the Chu Lai of General Krulak, is gone. And we are all the better for it.

I am exhaling now.

Rick why did you come to Casablanca? “For the water” Water, there is no water in Casablanca? “I was misinformed”

And so were we ALL….too many times!

Love beads? And you taught me never to bury the lede…

two paper towels of tears. Thank you, Fred.

Tom

Chu Lai absolutely changed me. There during its latter breaths of 1971 and witness to our “good luck” Chu Lai gift to the ARVN, a military base having been run-over by a fearsomely driven, roof-peeling Typhoon Hester 10/23/71. I met a few ARVN in the transition – so young they were – I walked away thinking, “you’re fucked.”

When I came home I wasn’t about to forget Vietnam. Some of it took longer to voice. U.S. pollution poisoning everything. Stuffed stacked body bags from MaryAnn, upside down dead men hanging along QL 1 in An Tan. Trailing a convoy, watching our troops tossing smoke-canisters into homes for laughs. Confronting my own sudden urge to kill because I could. The running nose of the heroin addicted, the missing face of a fellow soldier.The first shock of seeing the orphans and being pulled aside by Sr Yvonne, “the children-American fathers”.

I wore those US army Vietnam-fatigues til they rotted off me in the late 70’s. I spoke of the orphans, like so much of Vietnam – innocents caught up in something beyond their control and being thoroughly fucked by America.

The orphans, always the orphans. They opened my stone-cold heart. I have been and shall remain forever thankful.

https://www.facebook.com/pg/Van-Coi-Orphanage-Chu-Lai-Vietnam-180125072006537/photos/?tab=album&album_id=180136085338769

LOL, Chris. I bet you were looking for a hyperlink on THAT ONE. This is long form J; gotta tease out the goodies a little at a time. Now that I’ve put the bait out there, you’ll keep coming back for the payoff. Patience. It’s gonna be good when it gets here. Thanks for reading!

Hard to even imagine you with a stone heart, Tom Brogan. It’s a wonder how we missed each other in Chu Lai in 1971. But Heaven had a plan for us to become acquainted and I am thankful for that. Thanks for your inspiration and help, always. I look forward to meeting you soon.

I read the Bracatelli file because I am a Miles Junkie but followed this link because I am an Iraq Vet and I just wanted to say thank you for writing this. I am too young to have any memory of the Vietnam War but I can say from personal experience the “misinformed “ part I definitely get.

I have often wondered if I would ever go back to Baghdad down the road if times were better there. I still don’t know if I could, but I hope and pray that one day peace will make it possible.

P.S. What’s this about the Army and “love beads” – would love to hear that story.

Stay tuned Liz. The absurd story of my court martial is destined for this space in the near future! Be patient with me, because my writing will have to get to a whole other level to do justice to the human comedy involved. Thanks for reading.

On this Memorial day we thank you for your service once again, Mr. Fred!

Thank you for your support, Felix. Recently, I came across an old letter I wrote to BW, January, 1970, while at Ft. Bragg, NC. I wrote that Linda told me about the birth of your first child. Memories……

Since I served with the American Red Cross in Vietnam as a “Donut Dolly” from 24 July 68 – 2 Aug 69, I’m intrigued and touched by all of your memoirs. I arrived to serve with the Americal Division (my 3rd and last VN assignment) in Feb 69 where I stayed until I DEROSed. There are so many vivid memories forever engraved in my mind and heart from our daily runs out to the 196th, 198th, and 11th Brigades in Hueys and LOHes…Your photographs are poignant reminders of the ways things (and we) were over 50 years ago…My free time—usually on weekends and when we were grounded for bad weather or security reasons—was spent in the 312th Evac wards, doing our best to comfort the patients there, many of whom would never go home again. We tried our best to be “A Touch of Home in the Combat Zone”. Btw, I lived in Trailer #1 with no air conditioning at all….just an occasional dry breeze at night made it thru the tiny screened windows. There was a metal thermometer nailed on the wall behind my cot where the red mercury was stuck between 110-120 degrees….which was the maximum on the gauge…Any overhead chopper now triggers the same response in my head: “Time to jump in and head out to the Firebases and LZs to cheer up the guys.”…….

Wow…thanks for the info! I was there from Apr 68 – Apr 69 and my chopper company (71st AHC) was headquartered right on the beach. Lots of memories good and bad from those days.

“Larry:” Thanks to you and all the DD’s for your service and support. The work you did, the solace you provided, will be remembered forever. http://vietnamreturn.abatemarco.com/2018/05/28/american-women-who-served-in-vietnam/

Thanks for the history especially of the 312th/91st EVAC hospital. I was a lab tech when it was known as 91st from10/69 to 10/70. Many memories of lab parties and the private beach and the rush of getting blood to ER and surgery. Our lab officer Dr Contin, from Puerto Rico who always complained of having to be in VN, as we all did but more than the rest of us. I often wonder how the Drs and nurses are handling their PTSD from working with the trauma they saw with the wounded. I haven’t heard have you?

Phil: I wish I knew more, but I don’t. Linda Van Devanter wrote the definitive Vietnam battlefield nurse memoir. Called Home Before Morning. Harrowing and heartbreaking.

CHU LAI, THANKSGIVING DAY, 1967 TILL JAN 21 1969 23RD ADIN CO. AMERICAL DIV, WHAT A TIME,WHAT A PLACE, MORE STORIES AND MEMORIES THAN I HAVE ROOM FOR, BEACHES BEYOND COMPARE, HOT SHOWERS DOWN BY THE AIRFIELD IF YOU COULD GET THERE, AMMO DUMP GOING UP TET 68, I HAVE LOTS OF PHOTOS MANY OF US GOT GREAT CAMERAS AND DOCUMENTED OUR LIVES THERE.

I In Country at the 91st Evac. Hospital June 1969 while the 101st Air Borne was still assigned in Chu Lai. Subsequently the Americal Division replaced the 101st. Memories, In coming choppers either gunships, Medevac carrying the wounded and or KIA’s was a tough for a lot of us at such a young age. Great memories of those that I served with and the times we had together to hide the memories of casualties of war. Two years ago wife and I revisited the Vietnam Memorial Wall and brought back a lot of memories. I’m still trying to decide whether to return to Nam.. May be in a couple of years? In hind sight I’m proud to have enlisted and serve our great country!!