Today, Memorial Day, or anytime you salute those who served — in Vietnam and elsewhere — also remember our sisters who went to the field, and some who did not return.

Night-walking The Wall—the Vietnam Veteran’s Memorial in Washington, DC—was eerie. Not at all the majestic daytime experience. In the light, this singular ebony ediface looms as a world until itself. A rock-solid granite-garden fused in silence. The Wall’s power and its beauty has always been its massive stillness. Ever since it went up, I’ve mulled the irony of this semi-subterranean monument to nearly 60,000 US military dead. Since day one in 1982, it remained out-of-sight and out-of-mind to members of Congress whizzing their way up Constitution Ave to the Capitol.

This soft and gentle spring evening, however, The Wall was one with the night. This was my first visit in more than a decade. My recent return to Vietnam was still a fresh memory. This time, I felt I had come home, fully. School children whispered along The Wall’s path. I overheard one teen say that her grandfather’s friend was memorialized here. Yup. The Vietnam War was that long ago.

My wife and I had never been here together. We walked without words; listening. The silence spoke volumes. Then I steered us to the Vietnam Women’s Memorial, a larger than life, one-ton black bronze sculpture of three female military nurses in a group pose. It’s barely a quarter klick away from The Wall. There, we overheard a 20-something tour guide correctly inform her group that 8 women’s names are on The Wall—military nurses who died in the Vietnam War. I was impertinent enough to provide an addendum.

“There’s many US women who served and died in Vietnam who are not on The Wall,” I announced. “In particular, three were among the hundreds of women we knew in-country as ‘Donut Dollies’—Red Cross volunteers who went into the remotest field locations every day to bring a touch of home to lonely, scared, embattled GIs.” This group had no idea. They do now.

About 10,000 American military women served in Vietnam during the war. Mostly, they were medical personnel—nurses with officer rank. But the American Red Cross sent teams of young civilian women—all college graduates—to the Vietnam War between 1965 and 1972. The program was called Supplemental Recreational Activities Overseas (SRAO). These 627 women were the Donut Dollies.

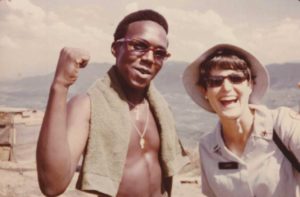

The Donut Dollies were from all over the US. For many, it was their first time away from home—just like the GI’s. But not Michele Marganski. I met and interviewed Michele in 1971, when she arrived on the Americal base in Chu Lai. I recall Michele as all cheery, pressed out neat and clean in her powder-blue pincord Donut Dollie uniform. A Fordham University math major, originally from Woodbridge, CT, Michele already had nearly two years in grade in the Philippines. She was a Peace Corps volunteer. She taught elementary school and worked on agricultural projects. Now she was in a war zone of her own volition. I was totally at sea as to why.

In 1981, the Donut Dollies staged a grand reunion in Washington, DC. There, I met Ann Alloway Stingle, Nancy Smoyer, Louise Bleakly and many others. They helped me gain an inkling of the Donut Dollies motivation. Smoyer, of Fairbanks, AK, described it this way: “I didn’t care about the politics of our involvement [in Vietnam]. When I learned that the Red Cross got us as far forward as women were allowed to go, except for journalists, that sealed it.” In 1968, Nancy was off to Vietnam as a Donut Dollie, “which I still refer to as the best year of my life…and the worst.” Indeed, Nancy. Been there, felt that.

In Vietnam, the Donut Dollies were the women who went to the field. They traveled by helicopter, jeep or truck. The Donut Dollies logged thousands of miles each month. More than 2 million it’s been calculated, over the life of the 7-year program. They reached out to men stationed at remote infantry camps and artillery bases from the DMZ to the Mekong Delta. Their job was to lighten it up for the guys with game-show style quizzes and the like. The tools of the trade comprised large urns of Kool-Aid, a canvas bag filled with construction paper signs and props reminiscent of elementary-school show-and-tell sessions. And a smile that needed to last until sundown.

The job entailed long hours and, often, a great effort to keep a positive outlook for the sake of hurt or troubled soldiers. The war and the men who fought it became an intimate part of their lives.

Every GI who ever encountered a Donut Dollie has a tale to tell about the girl next door who came out to the bush. The chance to take a day off from the war and hang out with a young American woman when you were scared, lonely and so far far from home was better than a visit from Santa Claus or the Easter Bunny. The next best thing to a week’s R&R in Hawaii with your girlfriend or wife. My Donut Dollie encounters were exclusively on the Chu Lai base. Mostly hanging out with Michele after hours at an impromptu and totally unauthorized bar that some of us created in back of the Divison’s G3 hootch. The so-called Hog Farm bar had a “no war stories” policy that was strictly observed by men and women alike. But Michele and her counterparts surely had a bunch.

Donut Dollies worked 12- to 16-hour days, seven days a week. They were often overwhelmed by their intended task and outnumbered by their audience. In an article I reported for the Associated Press in 1981, Ann Stingle recalled, “sometimes, we’d be getting to an LZ (landing zone) and the men would be just coming back from a mission. We’d throw out our program and just sit and talk. Maybe we’d hang around and eat C-rations with them or just respect that some men didn’t want to be approached. Sometimes the whole company would feel that way and we’d turn around and go away. It really hit home how little we could do.”

The late Lynda Van Devanter, a Vietnam Army nurse and author of “Home Before Morning”, told me in our 1981 interview: “I’ve talked to plenty of women who say, ‘I’m OK, no problems.’ Then they tell me they can’t drive on freeways and are startled by loud noises that remind them of rocket fire.”

Failure to recognize the symptoms of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, or efforts to deny them altogether, Van Devanter said, is not uncommon in women who served in Vietnam. “They equate it with mental illness. That’s not what PTSD is all about. It’s a normal reaction to a life-threatening situation. A war is a benchmark in a person’s life. It has to affect you somehow.”

Including the eight military nurses, a total of 67 American women died in the Vietnam War. Most of the civilians perished in the “Operation BabyLift” mission, when a plane filled with infant orphan children crashed after takeoff during the last days of South Vietnam’s fall. That was in April, 1975. One of those women was former Donut Dollie, Sharon Wesley. She stayed on in Vietnam after the US military pullout in 1973.

Three other Donut Dollies never made it home—Hanna E. Crews died in a Jeep accident in 1969. Lucinda J. Richter died of a viral disease in 1971. And Virginia “Ginny” Kirsch was murdered in 1970. They are memorialized on a plaque at the American Red Cross Headquarters in Washington, DC.

Of the nurses who died, First Lieutenant Sharon Anne Lane of Ohio was KIA (killed in action) during a rocket assault on the Chu Lai hospital in June, 1969. That attack on the Americal base is vividly remembered by Donut Dollies René Johnson and “Larry” Hines (Mary Laraine Young Hines) who were there.

“June 8, was the one-year anniversary of my college graduation,” recalls Hines. “We spent many volunteer hours —not part of our job description, but such a critical need—visiting the bedsides of the dying and terribly wounded who would not be healed or medevaced. Those hours still resonate in my mind and heart. They really brought the horrors of war right in front of my eyes, nose, ears, and hands.”

“I don’t remember being brave, and I truly don’t remember being afraid,” René Johnson has written. “I do clearly remember June 8, when the rockets sounded so close that I didn’t go to the bunker, but tried to get completely under my bed.”

So where are the Donut Dollies now?

René Johnson is often a “Story Teller” at the Women’s Vietnam Memorial and is planning her first return to Vietnam in 2019. Nancy Smoyer works tirelessly with veterans and their families. She describes her year in Vietnam as “the high point of my life” in a recently published memoir, “Donut Dollies in Vietnam: Baby-Blue Dresses and OD Green”.

Ann Stingle has written a play about wounded Vietnam veterans: “Still Beating Hearts”. Janette Maring administers a Facebook page for Vietnam veterans. Peripatetic Jeanne “Sam” Christie, seemingly hasn’t drawn a leisurely breath since she left the war. Of late, she was an advisor for the creation of New York Historical Society’s “Vietnam War” exhibition which is about to go on tour nationwide. World-traveling Louise Bleakly is a professional photographer.

Donut Dollie Paula Haley spent more than 20 years as an Air Force officer after her Red Cross tour in 1968. Recently she returned to Vietnam, where she was perplexed by the very modern and “un-communist” country she rediscovered. “One of the Vietnamese told me that Uncle Ho [Chi Minh] would be proud of Vietnam today. He only wanted one united country with people who were not harmed. This was a far cry from my thinking in 1968.”

Donut Dollies Dorset Hoogland Anderson and Mary Blanchard Bowe made a trip back to Vietnam in 2015 as part of a documentary film project directed and produced Anderson’s son, Norman. The Donut Dollies documentary is expected to be completed this year.

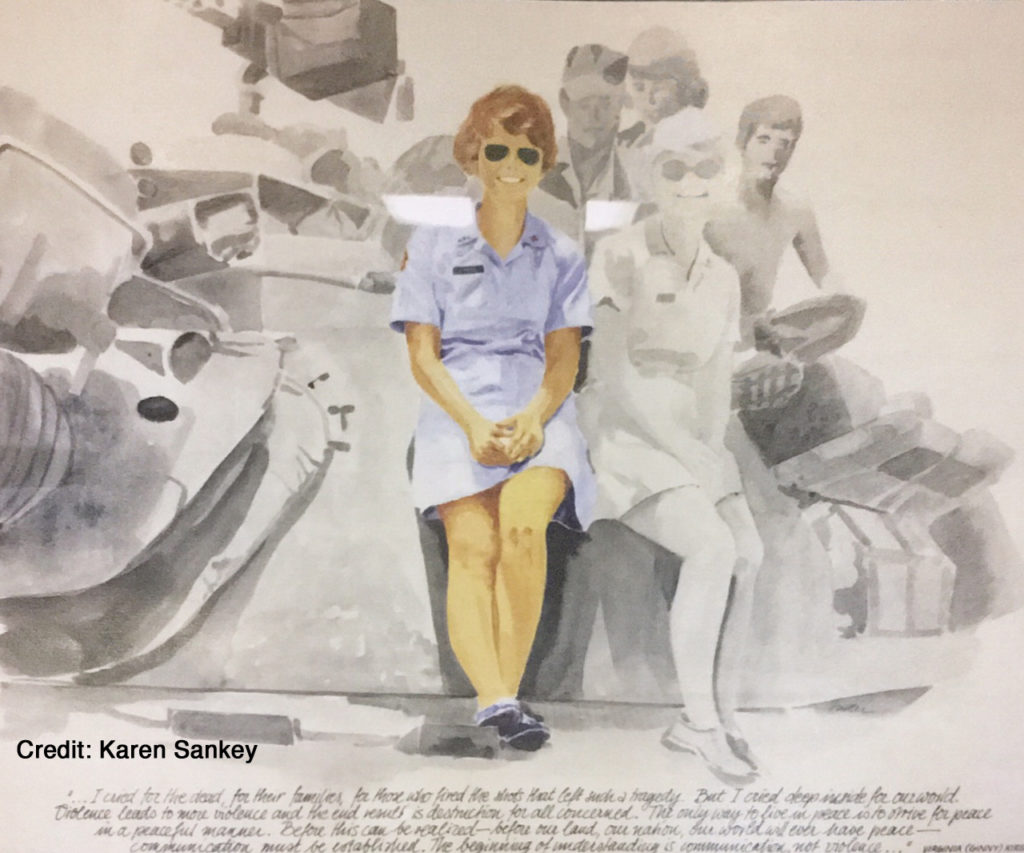

And the memory of Ginny Kirsch, who did not survive but a few weeks of the Vietnam War, lives on in Ohio. A highway near her hometown was recently named for her. And artist Karen Sankey’s painting—based on a photo of Ginny taken shortly after her ill-fated 1970 arrival in-country—captured her youth and enthusiasm for all time. Lest we ever forget.

Ever in our memories, brothers—and sisters.

Beautiful tribute to these amazing women Fred.

Thank you. And a million more words left unsaid today. Might I share this wonderful essay?

Doughnut Dollie 66-67

Joan McKniff

Fred, your writing stirs my emotions. Thanks to all these women. Beautiful!

Fred-more “unsung heroes” from a sad era!

Be my guest, Joan. Thanks.

Wow! Such a full and complete account of our service. Beautifully and sensitively written. Thank you, Fred!

You’re welcome and thanks same-same back to you for your service.

627 is the number, Felix!

Thank you with all my heart, Fred. I was one of the 627 who served in Vietnam. In my case, from 7/67-8/68. I worked with several women in your article, and was a story teller at our Memorial in its early years. In the Fall of 1967, the Danang Gang included Nancy, Sam, Louise, myself, and eight other amazing women. It was an extraordinary time and place. I went because of Marine amputees I’d worked with the summer before my senior year in college. One afternoon, they told me what it meant to them to see and talk with DDs out in the field. I knew then that I had to join the ARC and go to Vietnam as soon as I graduated. I did. I went through the First National Elections, Têt 68 in the middle of Bien Hoa, and the May Offensive of 68 very close to II FF at the eastern end of Long Binh.

Very fine piece, Fred, most illuminating. And you will possibly not be surprised that I know one of your Donut Dollies. More in personal message.

Thanks for reading it. Not surprised at all, Maura. I recall a while back introducing you to Ann Stingle and her play, “Still Beating Hearts”.

Kammy: Sounds like an amazing subset of the 627. Thanks for all you have done.

I served in 70-71….changed my life….I now speak at local high school US history classes. I visited the wall for the first time last year and will meet my DD friends in November for a reunion at Veterans Day in DC…..I had protested the war but never the soldiers……just like the GIs we all handled it differently….some of us just kept on with a ‘normal’ life and buried our experiences….for others, sharing helped the healing. I am now concerned with our exposure to Agent Orange and it’s devastating aftermath….

Nice hearing from you Ann. thanks for your update. We served the same years. Perhaps we’ll meet in DC.

My mother worked in Siagon in 1969 as a civilian for the US Army (she is an Australian ). There is limited information or reference to these women. Thank you for sharing the story, we need to tell them more often

Thanks Rebecca. How did you find my blog? Best, fa

Hi! I was researching for a trip i was making to Ho Chi Minh City to see if i could find out more information. I found that information to be very limited.

Yes. Sorry, Rebecca, this isn’t much of a travelogue. Hope your trip was an astounding success.