Today is just another spring day for most of us. But for Vietnamese, both there and here, April 30 is monumentally significant

My friend Oanh in DaNang took her family to the seashore this past weekend for an extended holiday. In Saigon, my fashion-forward friend Hang Nyguyen adorned the aerobics students she teaches in sportswear that she stylized as midriff-revealing replicas of Vietnam’s national flag. Today, all over Vietnam, people are celebrating a four day holiday in honor of Liberation Day. On April 30, 1975—30/4/75 as the Vietnamese write it—the last US helicopter lifted off the US Embassy’s rooftop in Saigon at 7:58 AM, as armored tanks of the North Vietnamese Army burst through the gates of the Presidential Palace to receive the unconditional surrender from the government of the Republic of Vietnam. The Americans were gone. The Vietnam War was over.

Now, 43 years later, a long, painful and recriminating process of unification behind them, the people of Vietnam celebrate their “30/4” holiday in various ways. Most Vietnamese are focused on today and tomorrow, not the past. In Hanoi, my young friend Chiang, whose passions run to Disney’s latest Avengers movie, KFC fast food and the Vietnam national soccer team, sees Liberation Day as a chance to relax at home while others travel to their hometowns outside the city. “Hanoi’s city center is quiet,” he says. “The main topic is not reunification or victory. Just where to go for holiday.”

In Saigon, which is to Hanoi what Miami is to Boston, the pitch is much higher. There are celebrations, fireworks and events galore to mark the occasion.

“This city is going so fast!” says Khoa Nguyen, founder and chief executive of In County Tours in Saigon, who plans to keep his holiday low key. “Everywhere is busy and expensive during these days. We just want to have family time, playing games, cooking.” His Dad, a South Vietnamese war veteran, visited from his home in the Mekong Delta over the weekend, but returned home before the festivities peaked.

One thing is almost certain, no one will be playing Irving Berlin’s White Christmas song on the radio in Saigon. Or, if they do, it won’t be for the same reason it aired on US Armed Forces Radio on April 28, 1975. Then, Bing Crosby’s out of season holiday croon was part of a coded message. Preceding it was a one sentence weather report: “The temperature in Saigon is 105 degrees and rising.” Thus began Operation Frequent Wind, a massive, chaotic, sometimes heroic, often tragic exodus of American and South Vietnamese personnel, rushing to the exit doors before the North Vietnamese sealed the country shut.

Hiding in plain sight in modern day Vietnam today is an iconic debarkation point of that evacuation that I came upon serendipitously one sunny Saigon morning during my recent visit. The BW and I were people-watching near the city’s Romanesque Notre Dame Cathedral when our laconic guide Kevin pointed out a modest nine-story office building nearby.

“Look familiar?” Kevin asked with his characteristically blank poker face. It took me a moment to filter out the glass skyscraper in the background that nearly camouflaged the building. But then I could mentally recall the image of a Huey helicopter precariously perched on a rooftop parapet, a stream of civilians climbing a ladder to get on board and leave Saigon once and for all. The image was captured by photographer Hubert Van Es on June 29, 1975 and, when published, became one of the signature photos of the evacuation of Saigon.

“We gotta get closer for a photo,” I said to Kevin. He raised an eyebrow as if to say silently, “Really? Okay, follow me.” We walked two blocks and in minutes, with a deft bit of grease to a doorman’s palm, rose in a modern elevator to a top floor, and then climbed a staircase one flight to a shaded roof deck where the parapet loomed before us.

In 1975, this nondescript office building was occupied by offices of the USAID agency and served as a so-called CIA “safe house”. Today, it remains an anonymous multi-use office building. There is no memorial here. No commemorative plaque marking number 22 Lý Tự Trọng Street as a historic site. For me, however, it was the Vietnam War equivalent of visiting Normandy beach or Flanders Field or Gettysburg. The sight lines are remarkably different now. Saigon has grown up around what was then number 18 Gia Long Street. And rumors persist that the building will be torn down any day now to make way for something much larger and more modern, like everything else in Saigon these days.

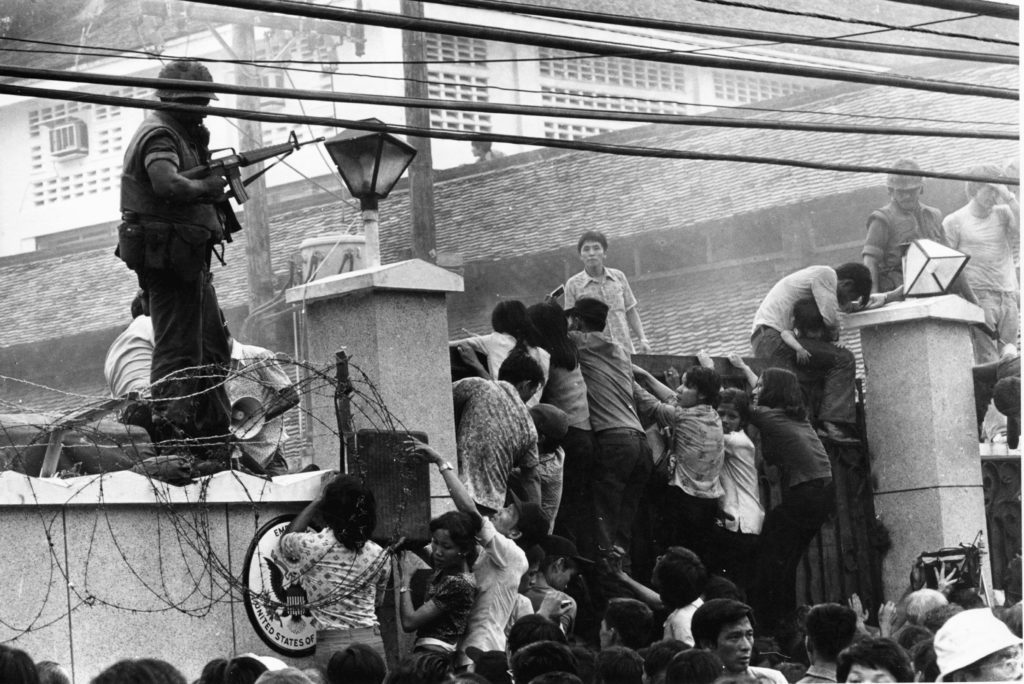

But most of the helicopter airlift occurred from the roof and parking lot of the American Embassy compound not too far away. From there, in less than 24 hours, a non-stop aerial procession of helicopters evacuated more than 5,000 Americans and over 1,000 Vietnamese out of Saigon onto US ships offshore. It is believed to be the largest helicopter evacuation airlift ever. The last 4 American casualties of the war—bringing the final total of US war dead to 56,559— were sustained during rocket attacks on the Tan Son Nhat Airport, which was destroyed as the city came under siege. Thousands more Vietnamese made it out of the country by all manner of boat and aircraft. South Vietnamese military pilots even crash landed helicopters of various size and description into the sea nearby American ships as they di-di mau-ed out of Dodge with their families and minimal possessions.

But tens of thousands of other South Vietnamese who wanted to leave–needed to leave for political reasons–did not make it out. Some estimates say that 30,000 or more were imprisoned and or killed following Saigon’s fall.

But tens of thousands of other South Vietnamese who wanted to leave–needed to leave for political reasons–did not make it out. Some estimates say that 30,000 or more were imprisoned and or killed following Saigon’s fall.

In the US and elsewhere outside of Vietnam, 30/4 is remembered by Vietnamese expats–but not necessarily celebrated as a holiday. Instead, April 30 is woefully called Black April or Day of Recrimination. In Dorchester, MA, Vietnam veteran Tom Brogan, who teaches English to the local Vietnamese community, notes that the many South Vietnamese army veterans there view this day sadly. “I understand their sadness of separation,” he says.

On July 2, 1976, the reunification of Vietnam was formally enacted. Saigon officially became Ho Chi Minh City. Healing, continues.

In the bank, the teller asked me if I knew what day it was. Acknowledging I did with, “sad day”, she told me each year her father goes downtown to the pictured (above) ceremony at City Hall, then “but I’m too young, I don’t know.”

Laura’s dad worked in that very building for the “parent company.” It was our first stop in Saigon after checking into the hotel. But they wouldn’t let us in. Kudos for getting on the roof!

Just saw the Daughter of Danang in Chicago. It was filled with students and afterwards we had a discussion. A lot of the students thought the daughter, (raised in the South in the US) was selfish. You could tell in the movie she found her birth mother cloying and suffocating. The older adults knew what was coming. The family asked her for money to help with taking care of her mother. During the movie we discovered the daughter was raised by a single abusive mother during her childhood. I suppose cutting off her newly found birth mother and her family in Vietnam was a survival tactic for her.

However, I still believe the daughter could send some money to the family.

My final thought is where in the world can you go and not expect people to ask for money when they find out you are American.

Bonnie–“Daughter From Danang” poignantly reveals how many facets there are to the war’s tragedies that continued to emerge after the last shots were fired.