Fifty years ago, on the last day of April,1975, the Vietnam War ended when the North Vietnamese Army overwhelmed Saigon. It was also the day that Tran Van Kim, then a fierce young Special Forces Major, made the hardest decision ever for himself and his family.

Tran Van Kim had a habit of running his hand over the shrimp-paste jars on the shelves of his Westminster, CA, grocery store. It was an absent-minded routine he liked to perform regularly. A simple act that often took him back to his childhood days at a store not very different that his father ran in the Mekong city of Gò Ðen in Vietnam. Kim regularly drifted back in thought to another decades-old memory, the last day of April, in 1975. That was when Saigon fell to the North Vietnamese Army. It is the day celebrated as the end of the Vietnam War. But to Kim, “30/4” was also the day of his most life-changing decision.

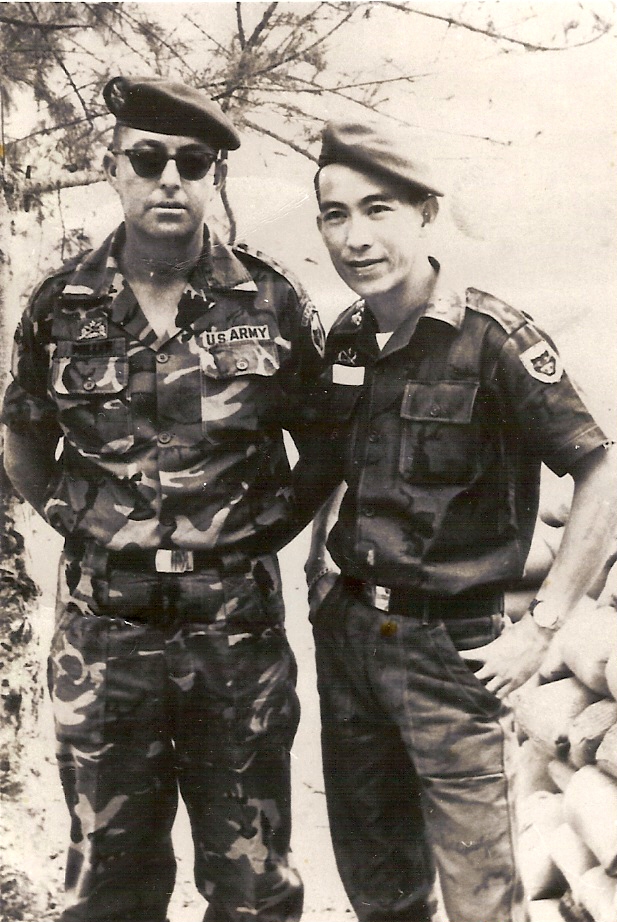

Kim was then a 38-year-old major wearing the maroon beret of the South Vietnamese ARVN Rangers. Standing erect and alert, only a few inches taller than the five-foot high sandbag wall that separated his men from an expected assault, Kim greeted the dawn of April 30,1975, with determination and trepidation.

The heat and humidity that typically swept up the Saigon River from the jungle lowlands had not yet suffocated the day. Kim’s sparse battalion of young special forces soldiers, many still teenagers, was nervous and chatty. But the Major was confident they were well trained and would respond valiantly to his commands in the battle which he knew surely lay ahead. The NVA was on the outskirts of the city with armored vehicles and Russian tanks moving steadily towards Kim’s artillery emplacement at the Royal Sports Racetrack. In better times, this was where the privileged middle class of Saigon gathered for social activities. At this moment, it was a key helicopter landing zone near the city center, certain to be a prime target of the expected engagement.

There was only one battle plan. Kim had orders to hold out and resist until told otherwise. The odds were overwhelming. But Kim was a career officer—Academy trained at Thu Duc following high school—who didn’t question his orders, ever. He expected the same obedience from his men—and got it.

As the sun climbed and the morning brightened, Kim began to perspire through his camo fatigues. The radio chirped on and off with staticky reports of the NVA’s infiltration of the once populous Cholon section. The area was now virtually abandoned by civilians who were fleeing the city. Within a few hours, Kim would be engaged in the most momentous battle of his career. There was no air support. No fall back position. The Americans were gone.

The day before, a coded evacuation message was broadcast on the US Armed Forces Radio: a weather report saying “the temperature in Saigon is 112 degrees and rising,” followed by Irving Berlin’s White Christmas song. That signaled the commencement of Operation Frequent Wind, a panic-filled 18-hour airlift evacuation that carried some 1,300 US citizens and a little more than 5,000 Vietnamese to safety. Another 65,000 Vietnamese left behind their homes and worldly goods, fleeing with barely the clothes on their backs by any means possible–fishing boats, barges, homemade rafts and sampans–desperate to meet a fleet of US warships anchored in the South China Sea.

The US Marines’ last helicopter, a Boeing CH-46 Sea Knight known as Lady Ace 09, had lifted off from the American Embassy compound at 755am. Kim, his men, and thousands of other Vietnamese civilians were on their own. But he didn’t fear for his personal safety. Kim had commanded battles from the highlands of Dong Ha near the DMZ, to the lowland rice paddies of the Delta. He had escaped death many times, none closer than at the fierce battle of An Loc in 1972. Walking ahead of his radioman, Kim turned suddenly as he heard a nearby explosion. Only a few paces away, Kim’s radioman lay dead. Half his face was blown off by an RPG round.

More recently, as part of the South Vietnamese 18th Division, Kim’s battalion fought courageously at Xuan Loc, just to the east of Saigon, helping to destroy three North Vietnamese divisions in the process. But the NVA was relentless. ARVN forces sustained nearly 50 per cent casualties. When they ran out of tactical air support, Kim and his unit was ordered to abandon Xuan Loc to the communists.

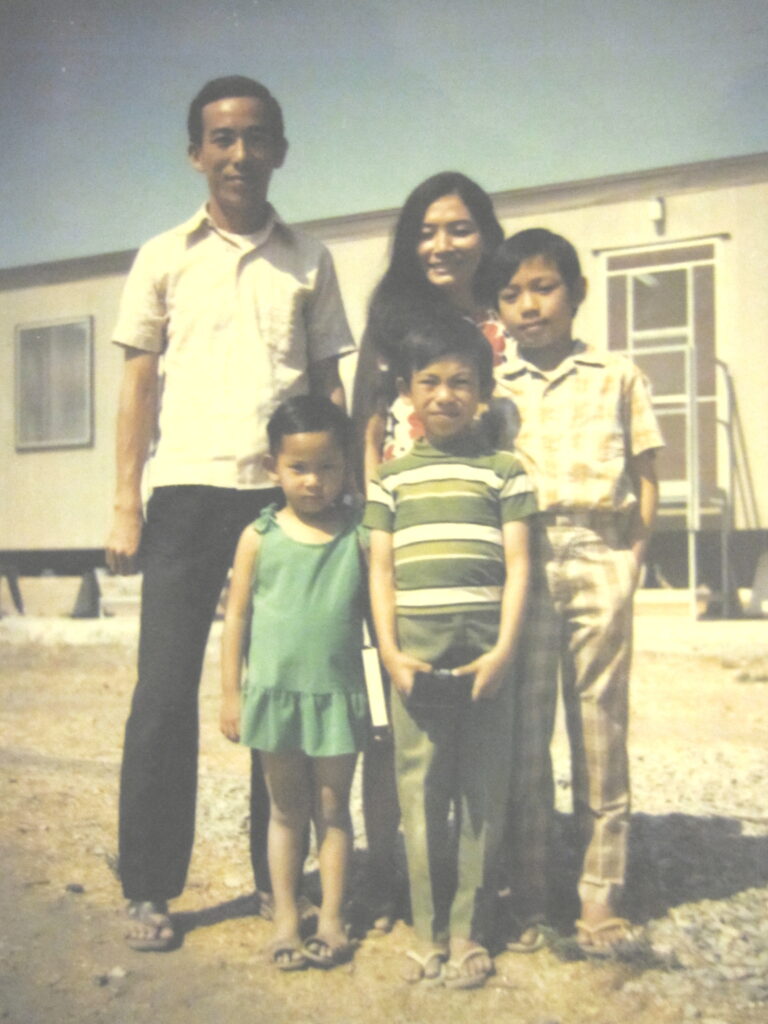

That was only days before. For this last stand on 30 April, Kim was defending home turf; the urban streets of Saigon where he lived with his wife and their three children, Tuan, Danh, and Chi. Kim’s wife Hon had left home at dawn that morning with their children and one small valise. Her mission was to escape Saigon—to leave forever their Vietnam home—by reaching a US Navy transport ship anchored a few miles outside Saigon harbor. It took hours for her driver to reach the Saigon River port, dodging crowds of panicked people streaming into the city from the outlying areas where the NVA had already surged through. At the wharf, a cargo scow, the “Jefferson,” listed dangerously to starboard from an overwhelming hoard of would-be refugees. Assessing the non-stop bedlam—loud, swift, and aggressive with unmerciful shouting and shoving—Hon told her driver to wait with the engine running. She battled her way to the boarding ramp towing behind her three children— their arms locked in a daisy chain. Hon managed to wave an official looking sheet of paper in front of one of the sentries and he signaled her forward. Turning to Tuan, her eldest son, Hon scolded in her sternest voice, “Hold onto each other. Whatever you do, do not let go of each other. I will be back with Father.”

With no time for a sentimental hug, Hon turned from the ship, jumped back in the Toyota and ordered her driver to head for the Royal Sports Club. The driver glanced back with disbelief in his eyes. But before he could audibly protest, Hon commanded, “Ditti Mau.” Go quickly!

At 10am, Kim and his men tuned in to a radio address from South Vietnam’s interim president, General Duong Van Minh. Minh had assumed his office only two days before; the rest of the South Vietnam government had already fled the country. Kim listened passively to the general’s televised message, which also boomed forth from all the telephone pole loudspeakers still operating throughout the city. ”To avoid further bloodshed,” Minh declared, “to prevent countrymen from continuing to kill and maim fellow countrymen, the government of the Republic of Vietnam has surrendered. Lay down your weapons. It is done.”

Col. Bui Tin of the North Vietnamese Army then took the microphone from Minh. Addressing both the people and the solders of South Vietnam, Tin said stridently: “You have nothing to fear. Between Vietnamese there are no victors and no vanquished. Only the Americans have been beaten. If you are patriots, consider this a moment of joy. The war for our country is over.”

The radio fell quiet. Kim looked around. The expectant gazes of his men pierced Kim’s stoic silence like a volley of perfectly targeted grenade shards. “Remain by your posts,” Kim suddenly barked, rousing his men back to their duties. Machine gun fire in the distance got louder and closer with each passing minute. All hope for victory was gone. But the fight was not yet ended.

Springing from the Toyota at the Royal Sports Club, Hon shouted her husband’s name. An ARVN MP stepped forward with his rifle pointed dead center at her heart. “Halt! This is a restricted area; You must leave.”

“Not until I see your commander, Major Kim. I am Tran Le Hon, his wife. I have an urgent message.”

Under guard, she was brought to her husband who turned white as a bedsheet seeing his Hon. “Why are you here? Where are the children?” he demanded.

“They are safe.They are aboard a US Navy ship preparing to leave the harbor.”

“And that is where you should be too. With your children,” reprimanded the Major.

“With your children; with our children,” countered Hon. “And you must return there with me. This war is over for you. Life in Vietnam is over for our family.”

Hon and Kim faced each other silently, reading each other’s thoughts. Words were not necessary. It was clear that Hon would not leave without her husband, in which case, their children would wind up orphans in a world beyond any familiarity. If Kim and Hon stayed, he would certainly be arrested, imprisoned, likely tortured and perhaps murdered by the NVA. Her fate would not be much better.

“You must choose between your duty to a lost cause, or a future as the father to your children,” said Hon at long last.

At precisely twelve noon, Kim turned to his executive officer and issued his final orders. “Have the men abandon their positions. They should drop their weapons, shed their military uniforms, burn their ID papers, and hurry to their homes or into hiding. The war is over for us all.”

Kim stripped to his underwear and joined his wife in their Toyota. He retained his Colt automatic sidearm, firing the handgun into the air to disperse the crowds congesting the streets as they drove. They reached the Saigon River just as the Jefferson’s dock lines were loosened. The sentry recognized Hon and waved her and Kim aboard.

It took Kim and Hon two hours to find their children, huddled and crying in the dark below deck. And it took ten years for them to rebuild a life in the USA. But for decades hence, Kim had trouble smiling, remembering always 30 April 1975, as the day he lost his home country.

To the people of present day Vietnam, “4/30” is a holiday of joyous celebration. It is their Independence Day on par with our Fourth of July. There are extravagant parades, wondrous aerial light shows of swarming, synchronized drones, feasts of holiday foods at home and in the streets.

But in Vietnamese expat communities like Kim’s in Orange County, CA, and others in Oregon, Minnesota, Texas, Massachusetts, and elsewhere throughout the USA,. 4/30 is a dark day of recrimination. “Every year on April 30, I am mostly sad,” Kim once noted. “I think about the loss of our South Viet Nam, our home. When the communists took over, they took everything from us.”

Kim passed peacefully in 2024. His wife Hon died eight years before. This year, his family marked their flight from Vietnam 50 years ago in ceremonies held aboard one of the aircraft carriers of Operation Frequent Wind, the USS Midway, which is currently decommissioned as a museum in San Diego Harbor.

Kim’s memory of 30/4 lives on.