August 18, 1969, fifty-five years ago today, I was supposed to be at the Woodstock Festival in upstate New York with my buddies. But instead on that sultry mid-summer morning, I was in Brooklyn, where I took my first military steps on the way to Vietnam.

As the sun rose on August 18, 1969, the Woodstock Music & Art Fair was coming to a close in Upstate New York. That’s where I had expected to be on that sultry mid-summer Monday, along with my buddies, Charlie Boy, and Vinny D. But that plan went belly up thanks to the “Greetings” letter I had received a few weeks earlier from Uncle Sam, informing me that my Army induction date coincided with the concert. So instead of grooving out with 500,000 hippies awash in “peace. love and music,” I found myself strung out and hung over in the last place I ever wanted to be: Brooklyn’s Ft. Hamilton, a languid, postage stamp of an Army base in the shadow of the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge. Befitting its role as a military chaplain school, it was church quiet on the base. But Ft. Hamilton was no pastoral refuge for me and my aching hangover. A major induction point for Army draftees, I was there for my military debut.

Big brother Frank drove me there in his five year old classic Buick Riviera, which we called the White Whale. We arrived early: 7 AM; Frank had wanted to beat the rush hour traffic on his way to work in Manhattan. As he drove, I glowed with pride watching Frank’s slender hands glide over the highly polished walnut steering wheel. I was nuts about that damned car, maybe even more than Frank. Each week that summer, as the clock on my civilian life ran down, my most cherished distraction was to painstakingly clean and shine the Riviera down to Q-tip detail.

On Friday afternoons, I’d set up a transistor radio in our driveway, chill a six pack of Carlton Black Label beer, and gather up a sleeve of saltine crackers and a hunk of cheddar cheese. For the nearly the next three hours, I’d make sweet, sudsy love to the Riviera with an elephant-ear sponge, Simonize paste wax, a damp chamois cloth and an aerosol can of Lemon Pledge. About the time I rinsed the red Brillo soap off the super-wide gangster whitewall tires, Frank returned home from his TV-producer job at CBS. He’d inspect my work and flip me a couple of singles. And, if I wasn’t too tipsy, and he didn’t have a date, he’d let me take the Whale out for a spin.

Frank was six years my senior but we were linked by a special closeness. Growing up, we shared a bedroom in our parents’ modest two-family home in the Gravesend section of Brooklyn. I doted on everything in his life, from his love of Beach Boys music to his fetish for shopping the one-of-a-kind rack at Bloomingdale’s department store. Frank read Esquire magazine; I read Esquire magazine. He wore Bass Weejun penny loafers, I wore Bass Weejun penny loafers. Frank’s favorite TV shows—Peyton Place and The Twilight Zone—became my favorite shows, way before I could figure them out.

I’d often adopt jokes and anecdotes I overheard from Frank that spoke of life beyond our insular Brooklyn neighborhood and Italian-American heritage. I’d pass these on to my friends as if they were my own. I was delighted whenever Frank had the time and inclination to include me in his life. Like the weekend when Frank purloined my Madras plaid golf jacket, which I had just purchased at the Campus Closet shop near Brooklyn College. For the first time, Frank was paying me props like a peer. It was a validation I had longed for and I was ecstatic. It almost didn’t matter when he returned home with the jacket in tatters from a bar brawl.

For most of my adolescent life, Frank had been my protector; in particular, a shield against our stepmother Phyllis’ wild emotional mood swings. Periodically, with the slightest provocation, she’d lose her shit and bilge forth tantrums born of frustrations about her loveless, childless life as a second wife. When she rained terror on our household, I’d cower. But Frank stood up to her cooly and defiantly.

“I’m calling your father,” he’d tell her, the receiver of our wall phone in his hand. His threat worked every time. Like the miracle of sunrise, she’d simmer down and domestic peace returned. Frank never had to dial the call.

That steamy morning at Ft. Hamilton, however, even Frank couldn’t save me. There would be no reprieve. At the H-hour of separation, stepping out of the Riviera, I was speechless with regret for what I was leaving behind: family, friends, and Natalie–my newfound love. And I was downtrodden with guilt, sucking on the bitter knowledge that I had only myself to blame for my fate.

I looked at the Ft. Hamilton administration building, then back at my brother. Never leaving the driver’s seat, Frank signaled his farewell with a silent, sympathetic shoulder shrug. Hope for the best; prepare for the worst, his body language said. I was wordless in return. A sudden, clear picture of my situation came into view. I was about to be sworn in for a two-year stint in the Army, unlike so many of my contemporaries who managed to avoid the draft and the war.

At the time, approximately 27-million baby boomers—all male US residents aged eighteen to twenty-five—were required to register for the Army draft. However, only a fraction actually served or was called. The bulk of the 10-million member US military, including the 3.5-million sent to Vietnam, were volunteers. Only about a fifth of the armed forces were draftees. And merely one in three of those went to the war: about 650,000. Draftees like me were a minority in Vietnam—though their casualties were proportionally higher.

None of my friends or relatives served full time in the military during the 60s. And they were typical. Fifteen million of my generation received deferments for reasons of poor health or injuries, family hardship, religious beliefs, military sensitive jobs, criminal records or—the gold standard which accounted for the majority of deferments—college studies. A few hundred thousand became “draft dodgers;” they openly refused military service risking prison, or skipped out beyond Uncle Sam’s reach to the likes of Canada, Mexico and Scandinavia. But the vast majority of my demographic—middle class, college-eligible, urban white males—never came close to seeing military service, let alone Vietnam. The majority of Americans who fought in Vietnam were poor or working class, meagerly educated, and from rural towns and farming communities or urban ghettos. Middle class, suburban white guys in the draft ranks were rare.

Some who beat the draft, like my brother Frank, finagled their way into homebound National Guard units. Following eight weeks of basic training at Fort. Dix, NJ, Frank lived out his military service by occasionally turning into a weekend warrior. He attended monthly meetings at the Park Avenue Armory in New York City, and spent two weeks each summer training at an Army sleep-away camp. Frank learned to be an Army cook and served his time turning out vats of pasta sauce and trays of oven-roasted bacon for 500.

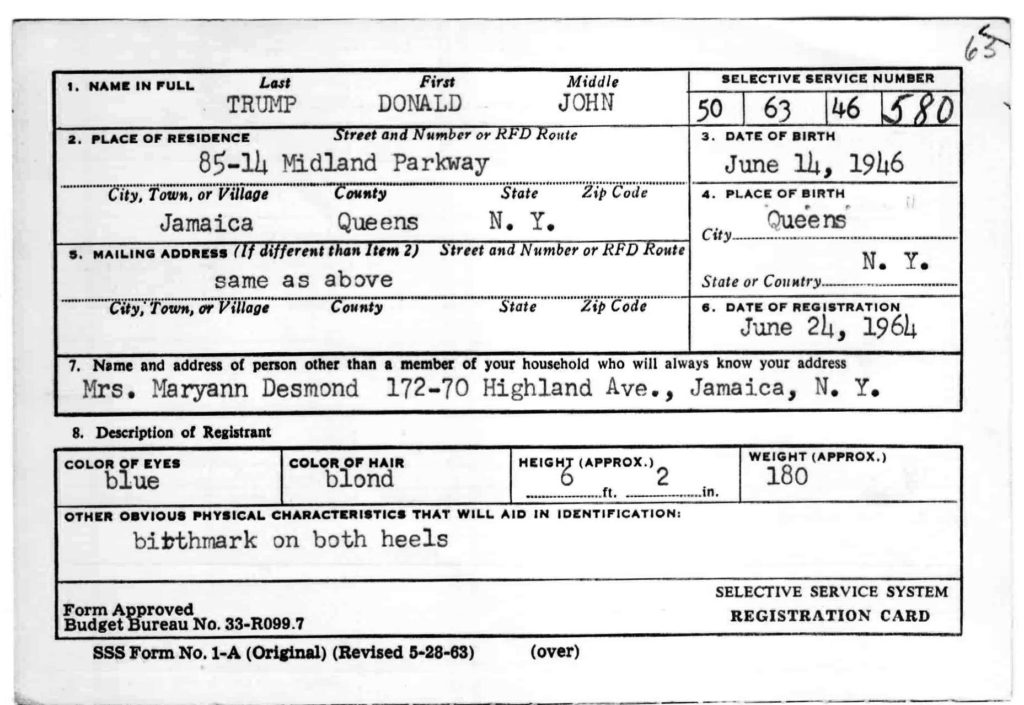

HELL NO; THEY DID NOT GO: Nearly every young American male was required to register for the military and carry his draft card……

So what was my problem? How come I wasn’t able to pull off what most of my contemporaries did? Why did I wind up in the Army—and eventually Vietnam—when so many others did not? All my deferment attempts were epic fails. The rudderless one step forward, two steps backward course I had plied since high school led me to the threshold of the Ft. Hamilton induction hall where I stood that morning 54 years ago, clutching with a sweaty, frightened death grip, one change of underwear and a toothbrush in a brown paper bag. Nineteen years old and seriously hurting from a week of subsisting on booze and amphetamines, I was desperate for relief from the intensifying morning sun, which blazed down on my shoulder-length hair, virtually reigniting my hangover.

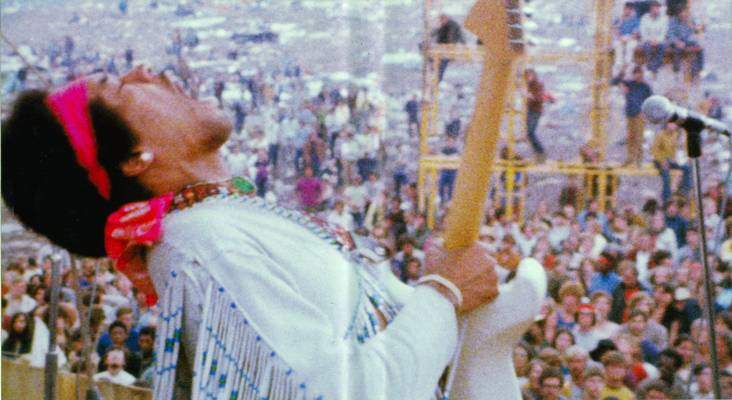

As Frank wheeled the Riviera out of sight, I stepped into the processing center, dizzy with dread. It was cool and quiet inside. In short order two dozen other recruits showed up. I peed into a cup, was instructed to raise my right hand, and recited a 72-word enlistment oath. Then, just as Jimi Hendrix turned the Star Spangled Banner into a plaintive psychedelic anti-war anthem at Max Yasgur’s Bethel, NY, farm, with my right hand raised, my left hand over my heart, facing an American flag draped on a wooden pole, I took the proverbial step forward and began my journey that would eventually snake its way to Vietnam.

Woodstock was history, and so was my life as a civilian.

More things here I did not know!!! Where was my head in 1969 ???? Love you my dear brother.

Very interesting. Luck of the drawer in my case was a 321 while a neighbor pulled a number in the lower third and promptly joined the National Guard. So, my main memories of `69 were working a summer job at a supermarket, watching 2001: A Space Odyssey on the Quad my first night as a freshman at Syracuse University and experiencing all hell breaking loose in my high-rise dorm when the Mets won the World Series. My freshman year ended two weeks early in May, 1970, when other freshmen were killed at Kent State and rioting at our campus closed down the school. Fred: thank you for your service. Too bad it was all for nothing.

Michael: Nothing is for nothing.

Love you too, cara sorella. Let’s compare notes real soon.

I was drafted in 1968 after leaving a Catholic seminary after 3rd year of college and then bumming around after 1 semester at public University. My dad gave me about as much direction as yours. Ended up getting a Chaplain Assistant MOS and spent approximately 5 weeks at Ft. Hamilton August 68 before getting orders to the ‘Nam. Ft H was the best Army assignment in the world as far as I was concerned, a Missouri hick who had never been to NY. ALSO SAW 2001 IN Manhattan with my soon to be fiancee who came to visit me one weekend.

So Fred, do you think we were “unbrave” for answering the call even if very reluctantly. I wondered so at that time, but, with many years of reflection and contemplation I have grown to accept and even find pride in the service we gave.

Gives a whole new meaning to stay in school, kids. Enlightening, as always. I dare say you might not be the man you are without all of the good, and bad, experiences. But who knows. Thanks, Fred.

Brave or courageous I was not. Lost and confused. All wars are heinious; this one was additionally unjust and politically reprehensible. I give thanks every day that I am lucky enough to be here to tell about it, and I cry everyday for the millions who are not.

No telling what the course would have been for fabatemarco had the butterfly not flapped it’s wings in 1969. Unlikely to have met the BW, so not complaining.

My experience with the draft and the war in Viet Nam was quite a bit different from yours. I spent most of my college years dating a very nice young lady and studying a lot. I was going to go to graduate school, get a master’s degree and teach English Literature. How naive. By the spring of my senior year (1970) my college had erupted in anger at the war and I was thinking a lot about it. I was scared. My lottery number was 135. For me, too close for comfort. I talked to a lot of my classmates and many of them confessed that they had gone down to the local National Guard office and enlisted. I was not crazy about this option. But one afternoon my fear of dying got the better of me and I drove down to the National Guard office and met Major McGuire (not Barry McGuire). No finagling, no Dan Quayle maneuvers were required–he signed me up on the spot. He then directed me to a supply room where they gave me a shit load of equipment. My roommate and I camped out with it in a verdant portion of the campus that night. One night not long after I heard cursing and screaming from a nearby dorm room, and I went out to see what was up. They were cursing about footage from Kent State, cursing at the National Guard. What had I gotten myself into?

I went to basic training at Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri, where it was very very hot. While it was objectionable to be ordered around and fire guns and march all over the place, Basic was tolerable. I told myself that it beat Viet Nam. Many of the trainees were guys like me–college grads who took the cowards way out. I have always been a shy guy, and it felt good to be able to sit down at any dinner table and talk about the common enemy: the drill sergeants. Also, I dropped 30 pounds and got into great physical shape.

When Basic was over and I got back to my unit I found that almost everyone was like the guys I met in Basic. I’m not proud of it, but most of us did as little as we could at the monthly meetings. The new trend of National Guard units being activated and sent to dangerous places overseas, never happened to us. If it had, we all would have been killed. We were pathetic excuses for soldiers.

Basic training was like being hit in the head with a shovel everyday. When it was over, you were a mess, but it felt so good that the head banging was done.

Bob… I checked with the judges, and you still get a thank you for your service! Hope you’re well.

Fred-my “get out of the draft card” was my new born daughter, Tricia-1/4/70. Unlike my father in WW2 who was drafted with two kids they never got around to drafting fathers of one kid for Nam. Being a father & supporting a family at 21 had its challenges but it was nothing compared to what you & many others had to live through. Thank you for your service!

Felix–Linda Tesorierio faithly kept me informed of the goings on among you and the other guys all through my army time. I still have letters referring to your marriage and the birth of your daughter. She also sent me clippings of the NY Mets march to the championship in 1969. I owe my mental health throughout my service to good friends like her and you and BW and so many others.